Digital storytelling in education: Design and development of pilot prototypes for KS3 students

- BJ

- 2023년 10월 28일

- 18분 분량

최종 수정일: 2023년 12월 13일

3.1.1 Fundamentals of data-based research: Approaching Grounded Theory

3.1.1.1 Introduction to grounded theory

Grounded theory, based on the ground-breaking approach of Glaser and Strauss, provides a methodological approach to the systematic analysis of data that facilitates the emergence of theories that are profoundly 'grounded' in the data itself (Glaser and Strauss, 2017, Charmaz, 2006, Corbin and Strauss, 2008, Birks and Mills, 2015, Bryant and Charmaz, 2007).

3.1.1.2 Principles and advantages of grounded theory

The core principle of grounded theory is the systematisation of data analysis. It not only focuses on a systematic description of phenomena, but also integrates predictive logical systems. By complying with this approach, researchers can identify patterns, behaviours and basic structures in the data, making it a powerful tool in various fields, including educational research (Strauss and Corbin, 1998, Charmaz, 2014, Suddaby, 2006, Heath and Cowley, 2004) .

3.1.1.3 Stages of analysis in grounded theory

Grounded theory involves a structured, incremental approach to data analysis (Glaser and Strauss, 2017, Corbin and Strauss, 2008):

a. Phenomenological analysis:

This primary stage aims to understand and interpret the main phenomena under investigation. The term "phenomenological analysis" is used to refer to an in-depth exploration of the core experiences and appearances extracted from the data. It's important to recognise that while phenomenology is a distinct qualitative method, in this context the term is used to emphasise the depth of understanding aimed for in the initial stages of grounded theory analysis (Creswell and Poth, 2016).

b. Category Relationship Analysis:

This stage emphasises the identification and understanding of relationships between different categories or topics that emerge from the data (Charmaz, 2014).

c. Theoretical Integrated Analysis:

The final stage integrates all the findings and summarises them into a comprehensive and consistent theory (Corbin and Strauss, 2008, Birks and Mills, 2015).

3.1.1.4 Implementation in this research

In line with the principles established by Corbin and Strauss (2008), this research project will use the constant comparative method. This iterative process will involve the continuous comparison of new data with existing data. Through this method, the research anticipates building bridges between the tangible and abstract intersections between education and technology (Glaser, 1965, Lincoln and Guba, 1985). By 'abstract intersections' it refers to the more in-depth, frequently sophisticated points at which concepts of education and technology converge, overlap and influence each other. For instance, how technological advances might transform pedagogical methods, or the impact of digitalisation on learning outcomes (Selwyn, 2010, Kirkwood and Price, 2014, Livingstone, 2012).

3.1.1.5 Transition to the iterative design process

Following grounded theory methodology, the findings and insights will inform the iterative design process (Braun and Clarke, 2006). Grounded theory provides for the design to be closely grounded in the data, making the design process more informed, relevant and effective (Preece et al., 2015, Sim and Wright, 2000). The following section, "3.1.2 Iterative Design Process", explores how this data-driven approach informs and enhances the design process (Buxton, 2010). Moving from a grounded theoretical framework to an iterative design process is particularly beneficial for this research because it allows the design to be rooted in real-world data (Cross, 1982). This is useful in that it enables the design to be based on actual data, meaning that the solutions or tools developed are not only theoretically sound, but also practically applicable and responsive to the actual needs and challenges identified in the data (Preece et al., 2015). Having established the theoretical foundation with grounded theory, the practical application of these insights will be explored through the iterative design process.

3.1.2 Creating digital narratives: The iterative design pathway

3.1.2.1 Overview

The iterative design process is a key feature of this research, providing a structured approach to refining and evolving the interactive storybook tool based on continuous feedback and evaluation. Iterative design refers to the process of completing a product or software by repeating a series of processes, such as ‘Requirement, Architecture (as a system configuration), Development, and Test’ before a final product is released in a new software programme or product development project (Mistrik et al., 2014). This is similar to an incremental approach that reduces the technical risks after product launch by more reliably planning the completeness of a programme or product by utilising information on customer requirements rather than initially determining the details of the new software programme or products (Hughes, 2003). ‘Evolutionary life cycle’ and ‘Rational unified process’ are other terms for iterative design process (Goodman et al., 2012). In addition, The Evolutionary Life Cycle refers to a development process in which the product evolves through repeated cycles, refining and extending its features with each iteration (Royce, 1987, Pressman, 2005, Sommerville, 2011). The Rational Unified Process is a software development approach that emphasises adaptability and flexibility to accommodate changes and refinements as the project progresses (Kruchten, 2004, Jacobson et al., 1999, Dutoit et al., 2007).

Goodman (2012) defines the iterative design process in three stages: ‘Examination, Definition, and Creation’, and emphasises the importance of accurately understanding the core of the problem to be solved, especially based on the data collected during the ‘Examination’ stage. This is in line with Peter's argument that focusing on accurately comprehending the information collected at the ‘Requirement’ stage while repeating each process of iterative design can develop a more complete product or software programme.

Deep insight into the iterative design process and its application in research

3.1.2.1 Understand iterative design for prototype development and data analysis.

Iterative design process: An overview

The iterative design process, widely used in software development and learner-centred design, is a repetitive approach that allows for continuous improvement and refinement based on feedback (Baxter and Sommerville, 2011, Norman, 2013, Bruckman, 1999, Kirschner et al., 2006, Squire, 2006). It consists of iterative cycles of design, implementation, evaluation and refinement. This approach enables the design to evolve and improve incrementally over time, ensuring that the final product meets user expectations and needs (Nielsen, 1994).

Application of the iterative design process in prototype development

In the context of this study, the iterative design process is applied in two main areas: the creation of the interactive digital storybook prototype for KS3 students and the collection and analysis of data (Venable et al., 2016). This iterative process, which focuses on feedback from educational experts and pilot testing, aims to enhance the usability and interactivity of the digital storybook. The ultimate goal is to adjust the design to further facilitate the development of KS3 students' language skills (Nielsen, 1994) (Baxter and Sommerville, 2011).

Iterative process in data collection and analysis

In terms of data collection and analysis, the study also uses an iterative process through a Delphi survey and an online focus group study. Each iteration involves collecting data, analysing responses and refining subsequent data collection methods and questions based on the findings. Through this method, the study's data collection becomes thorough and responsive to the evolving research context. As a result, the data obtained will be more comprehensive and relevant to the objectives of the study (Hasson et al., 2000).

The significance of the iterative design process in this study

Overall, understanding the role of the iterative design process is crucial as it shapes how the study develops its digital storybook prototype and collects and analyses data. This ensures that the research remains responsive and flexible, adapting to expert feedback and the results of pilot testing. Furthermore, the iterative design process enhances the reliability and validity of the study's findings by consistently reviewing and improving the research methods and findings (Preece et al., 2015).

3.1.2.2 Apply iterative design in the creation of digital storybooks for KS3 students.

Planning stage: Identifying curriculum materials and narrative elements

The iterative design process becomes an instrumental tool to ensure the effectiveness and relevance of the product to the target users in the context of creating an interactive digital storybook for KS3 students. Starting with an initial idea or concept, the first stage of the process involves careful planning. This includes selecting reading material pertinent to the KS3 English literature curriculum, exploring the narrative arc and vocabulary of the selected stories, and considering what interactive elements could be incorporated to engage learners (Druin, 2002, Carrol, 1999) .

Prototype creation: Integrating narrative and interactive features

Following this, a prototype of the digital storybook is created. The prototype at this stage is a basic version that includes the main narrative elements and creative writing as well as the interactive features utilising comment sections for user participation. The effectiveness of the prototype is then evaluated in a controlled setting, perhaps with a small group of students including a KS3 learner (Kafai and Resnick, 1996).

Feedback and refinement: Enhancing design with expert insights

The next stage is to refine the prototype based on the insights from educational professionals. This refinement may involve additions or modifications to the interactive elements, improvements to the interface to enhance the user experience, and potential utilisation of Open-Source Software as part of these improvements. The process of testing and refinement is repeated iteratively, continuously enhancing the design of the digital storybook (Nielsen, 1994, Preece et al., 2015, Shneiderman et al., 2016).

Embracing stakeholder feedback: From pilot study to iterative design

In this study, the iterative design process embraces the input from multiple stakeholders. The development of the interactive digital storybook prototype was conducted through a series of stages involving different stakeholders, starting with a pilot study that involved a small group of secondary students. Their insights provided a crucial user perspective and highlighted areas for improvement (Druin, 2002). Feedback from educational professionals was then incorporated into the development of the second iteration of the prototype. This combination of user experience and expert feedback ensures that the design of the storybook meets the needs of its end users, while maintaining high standards of pedagogical and technological design (Baxter and Sommerville, 2011, Norman, 2013).

Final refinement and evaluation: Enacting learner-centred design

Lastly, the prototype will be further refined based on feedback from a Delphi survey with digital storytelling researchers and an online focus group study with KS3 English teachers. This iterative, feedback-driven process will result in a product that effectively addresses its target audience while embodying the principles of learner-centred design, a core tenet of social constructivist theory (Vygotsky and Cole, 1978, Bruckman, 1999). This means that the digital storybook is designed with the learners' needs and experiences at its core, fostering an active learning environment where students can construct knowledge through interaction with the digital content.

3.1.2.3 Benefits of iterative design for prototype development and data analysis.

Enhanced Prototype Development:

The application of the iterative design process to the creation of an interactive digital storybook prototype in this study has several advantages. This approach, involving stages of design, testing, and refinement, can enrich the prototype's development (Nielsen, 1994). Feedback incorporated at each stage enhances the usability, effectiveness, and engagement of the storybook, creating a tool well-suited to its educational purpose (Draper and Norman, 1986). This aligns with the principles of social constructivist theory, which emphasises the active role of learners in constructing knowledge (Vygotsky and Cole, 1978, Palincsar, 1998).

Improved Data Analysis:

The iterative design process also benefits the data analysis from the Delphi survey and online focus group study. By incorporating the findings from these analyses into subsequent design iterations, this study can continually adapt the prototype (Buxton, 2010, Mayhew, 2008). This adaptation is based on in-depth insights into user behaviour, preferences, and challenges (Baxter and Sommerville, 2011), offering a dynamic and responsive approach to data analysis.

Risk Mitigation:

Furthermore, the iterative approach helps to mitigate the risks associated with prototype development. By identifying and addressing potential flaws early in the development phase, this study can avoid time-consuming changes later on, which is critical in the resource-limited educational context (Nielsen, 1994, McConnell, 2004).

Conclusion:

In summary, the application of the iterative design process to the development of the interactive digital storybook prototype and the data analysis process in this study provides a robust, learner-centred, and dynamic approach (Nielsen, 1994, Tripp and Bichelmeyer, 1990). This methodology contributes to the development of an effective educational tool and facilitates an in-depth and evolving understanding of learner interactions and engagement. Thus, it enriches the research findings of the study (Preece et al., 2015).

3.1.2.4 Challenges and limitations in using iterative design for prototyping and data processing.

Despite the many advantages of the iterative design process, it is important to acknowledge the challenges and limitations that arise when applied to this study, particularly in relation to the development of the interactive digital storybook prototype and the associated data collection and analysis processes.

Time and resource intensity

The iterative design process can be time consuming and resource intensive. The need to repeatedly test and refine the prototype could potentially prolong the development phase and thus consume more resources (Virzi et al., 1996). In a study with limited time and resources, this could be a significant challenge.

Obtaining comprehensive feedback

Obtaining comprehensive and actionable feedback at each iteration can also be challenging. This challenge is particularly pronounced when collecting data from the Delphi survey and online focus group study. It's important to ensure that the feedback collected is representative and comprehensive enough to effectively inform the redesign process (Hasson et al., 2000, Rowe and Wright, 2001).

Risk of design fixation

Although the iterative process is intended to produce an optimal final product, it can potentially lead to design fixation or a reluctance to make significant changes in later iterations for fear of discarding work already completed (Baxter and Sommerville, 2011, Jansson and Smith, 1991).

Overemphasis on learner-centred approach

The iterative design process is predominantly a learner-centred approach that could potentially neglect other important factors such as technical feasibility or scalability. While feedback from learners, teachers, and educational researchers is crucial, it is important to balance this with an understanding of the broader technical, contextual, or practical constraints (Nielsen, 1994, Preece et al., 2015).

Balancing Benefits and Drawbacks

In summary, while the iterative design process provides valuable benefits for this study in the development of the prototype and data analysis, it also presents certain challenges and limitations that need to be carefully considered and managed. This awareness will enable the study to effectively address these challenges, optimising the benefits of the iterative design process and mitigating potential drawbacks.

3.1.2.5 Role of iterative design in prototype development and data analysis.

Enhancing language competencies through iterative design

In this study, the iterative design process plays a central role both in the creation of the prototype of the interactive digital storybook for KS3 students and in the collection and analysis of data (Cross, 2021). At the prototype development stage, the iterative design process allows for continuous refinement based on the feedback, resulting in a final prototype that enhances the language competencies of KS3 students (Draper and Norman, 1986, Nielsen, 1994). This process allows the study to progressively improve the design, interactivity and usability of the digital storybook (Baxter and Sommerville, 2011, Shneiderman et al., 2016).

Iterative process in data collection and analysis

In terms of data collection and analysis, the iterative design process plays an important role in the Delphi survey and online focus group study (Hasson et al., 2000). By using an iterative approach, the study will continually refine its data collection methods, survey and focus group questions based on responses from previous rounds, ensuring that the most relevant and comprehensive data is collected (Linstone and Turoff, 1975). Furthermore, iterative analysis of this data can lead to deeper insights and a more nuanced understanding of the research topic (Gordon, 1994).

The critical role of the iterative design process

To sum up, the iterative design process is critical to this study, facilitating the creation of a learner-centred prototype and robust data collection and analysis methods (Baxter and Sommerville, 2011). It ensures that the research findings are valid, reliable and provide meaningful insights into the use of interactive digital storybooks for KS3 students (Nielsen, 1994, Jaspers et al., 2004).

3.1.2.6 Evolutionary model

The Evolutionary Model is a method of combining the iterative design process and the incremental approach (Pankaj, 2019). This is a method of dividing each stage of the development project into minute units, prioritising them, delivering them one by one to users sequentially, and improving the product or software programme based on feedback received from users progressively (Pradhan et al., 2020). Therefore, a small group of users start using a prototype of the initial product, rather than waiting for the final version. The users then provide feedback to the developer, and the prototype is enhanced gradually based on the feedback.

3.1.2.3 Key Features of the Iterative Design Process

A key factor in the success of this iterative design process is to accurately reflect rapid redesign and user requirements based on user testing and their feedback on the initial version prototype of the product (Justinmind, 2015). In addition, it has the advantage of repeatedly testing core elements to reduce the possibility of errors in the final product, while not having to invest large resources in one go to develop the desired product or software programme.

In the iterative design process, Mandel (2002) emphasises the importance of usability evaluation as the ultimate method to ensure that the product fulfils the requirements of users before launching it as an important evaluation method. It measures user behaviour, performance, and satisfaction in a quantitative and qualitative method, and conducts an initial usability evaluation when the interface of the product or programme is prototyped and configured.

In summary, iterative design process can lead to an enhanced final version of a tool or product and so this research project will follow the iterative design process to enhance a prototype of an interactive storybook for helping KS3 students to enhance their language skills. In addition, I intend to involve a group of participants consisting of secondary teachers and researchers in an iterative design process.

DESIGN

A digital storytelling resource design _ This research project designs a teaching and learning resource for creating digital storybook for enhancing language skills of KS3 students in the UK. In addition, the digital storybook includes creative writing utilising GCSE vocabulary list and collaboration skills.

PROTOTYPE

Initial prototype of interactive storybook _ An initial model is designed of a mobile storybook prototype including multimedia technologies and the features of interactive storytelling. It is also designed to reflect the card news format that can be supported in the first prototype.

EVALUATION

Feedback _ First feedback was received from expert commentator and Director of Study (DoS) through Research Degree Candidate (RDC)1 interview. As a result of reflecting their advice, this study has developed the intermediate version for RDC2 preparation. Ultimately, this research project aims to create final version of the interactive storybook through collecting the feedback of schoolteachers and education researchers.

In essence, the iterative design process makes sure that the research results, especially the interactive storybook, are not only theoretically well-founded but also practically feasible. This process, involving continuous refinement based on feedback, provides a mechanism for the iterative design process to produce a final product that is directly responsive to the needs and demands of its target audience: KS3 students.

3.1.3 An initial interactive storybook prototype (Creating digital narratives: The iterative design pathway)

3.1.3.1 Overview of the initial Interactive Storybook prototype

The decision to use an interactive storybook as a medium is based on the increasing ubiquity of digital narratives in modern educational contexts. Such storybooks have emerged as useful tools for increasing engagement and facilitating a variety of learning experiences (West, 2015, Rainie and Wellman, 2012). The initial Interactive Storybook prototype uses elements of digital storybooks to facilitate communication between learners as story creators in a mobile environment, providing a collaborative platform that's accessible anytime, anywhere (Robin, 2008; Sadik, 2008; Hwang and Wu, 2012; Park, 2011).

This prototype blends multimedia elements with traditional storytelling, providing learners with the ability to create and share original digital narratives that include edited or selected images, audio and video clips Lambert (Lambert and Hessler, 2018, Miller, 2019, Robin, 2008). Design choices, such as the mobile UI using the card news design, were carefully selected to promote an intuitive user experience in line with modern digital consumption patterns (Kim et al., 2020; (Krug, 2000, Wroblewski, 2012, Norman, 2013) (Preece et al., 2015, Tidwell, 2010).

The initial Interactive Storybook prototype is based on the elements of digital storybooks and has been designed with the intention of facilitating communication with participating students as story creators, anytime, anywhere in a mobile environment (Robin, 2008, Sadik, 2008, Hwang and Wu, 2012, Park, 2011). In addition, it combines multimedia elements and interactive features with traditional storytelling (Garzotto et al., 2010). Students participating in this programme can create their own original digital stories encompassing images, audio, and video clips they have selected or edited. As student authors, they can also share their stories with friends and family through the mobile sharing feature.

Fig.4. Cover page in iPhone

Fig.5. Cover page in iPad

The interface is mainly composed of mobile user interface (mobile UI) utilising the card news design (Kim et al., 2020). Each page can contain multimedia elements such as text, image, video, and voice, and it is possible to directly connect the original sources of each piece of content through their URL addresses. On the horizontal line fixed at the bottom of each mobile page, students can use 'like, comment box and an external sharing feature', which reminds users of the possibility of connecting this digital storybook to social network services. After learners generate their creative sentences in the comment box at the bottom of the mobile page, their writing combines to compose a new story as guided by the programme leader.

Fig.6. Text page and voice playback function

Fig.7. Image + text page and original source

Fig.8. Video + text and original source

Fig.9. Comments box

The original source of each image and video can be found at the bottom of the mobile page. when the icon representing the original source is clicked, it is directly connected to the corresponding original webpage to clarify the intellectual property (IP) rights of the connected images and videos.

By clicking the speaker-shaped icon at the top right of each mobile page, users can listen to the recorded voice. In the editing mode, the programme leader can add texts, record sounds, save images or video clips and change the layout of the mobile page through a simple tab-based interface.

3.1.3.2 Interface characteristics

The prototype is presented in a mobile book layout, reflecting the emerging trend of mobile-first design in educational technology (Wroblewski, 2012, Johnson et al., 2010). This multimedia book format is designed to be accessed via mobile phones, iPads and Tablet PCs, providing a comprehensive multimedia experience (Mayer, 2002, Moreno and Mayer, 2007). A key feature of this prototype is its interactivity. Learners can not only passively consume content, but also actively participate by writing and modifying their creative sentences in real time, illustrating the concept of interactive digital storytelling (Sims, 1997, Laurillard, 2013, Miller, 2014, Iurgel et al., 2009).

A storybook in a mobile environment

Digital storytelling prototype is designed in a mobile book layout that can be produced and access in a mobile environment.

Multimedia storybook

It is a multimedia book format that can be accessed with mobile phones, iPads, and tablet PCs, so you can use multimedia technologies such as voices, videos, images, and texts.

Interactive feature

In addition, students participating in the digital storybook programme can write their creative sentences in the comment box in real time and modify and upload their sentences at any time, which means the digital storybook project emphasises an interactive feature.

In summary, this Digital Storybook Prototype aims to help programme leaders work with their learners to create digital storybooks using voices, videos, images and comments in mobile environments such as mobile phones and iPads.

3.1.3.3 Intellectual Property and Ethical Considerations

In terms of ethical considerations, the prototype provides clear source references for all multimedia content (Crews, 2020, Council, 2000, Ess, 2013, Consalvo et al., 2011, Ribble, 2015). Direct links to the original websites are embedded to provide clarity on intellectual property (IP) rights and to promote a culture of respect and responsibility among learners (Aufderheide and Jaszi, 2018, Willinsky, 2006, Greenhow et al., 2009, Ohler, 2011).

3.1.3.4 Future Directions and Conclusions

Moving forward, the prototype will undergo a series of in-depth user reviews to collect feedback and identify refinements (Rubin and Chisnell, 2008, Dumas and Redish, 1993).

This iterative approach, based on the principles of user-centred design, will enable the tool to remain relevant and effective for its target audience: KS3 students (Draper and Norman, 1986, Nielsen, 1994). The ultimate goal remains to provide an enhanced tool that facilitates not only learning, but also the creation and sharing of knowledge in the digital age (Selwyn, 2016, Collins and Halverson, 2018, Rheingold, 2012, Jenkins and Ito, 2015, Scardamalia and Bereiter, 2010, Cuddy, 2002).

3.1.4 An intermediate Interactive Storybook Prototype (From the theoretical to the practical: The Evolution of the Interactive Storybook Prototype)

3.1.4.1 Overview

This section is a preliminary phase in research to explore the various competency elements of digital storytelling that the intermediate prototype has included. This preliminary phase in research could be useful in consolidating a topic by expanding or narrowing its scope (College, 2021). A core element identified by preliminary research will be evaluated by education experts through Delphi survey. In addition, based on their feedback, the study will explore the feasibility of utilising a final version of the prototype. An intermediate prototype based on Google open sources is expected to help schoolteachers to create interactive storybooks using a variety of media for students without digital storytelling tools.

3.1.4.2 The preliminary research in various elements of digital storytelling

Digital storytelling includes the elements of digital literacy focusing on how digital media tools such as social media platforms and websites interact with society in general (Grisham, 2021). In addition, media literacy is being emphasised throughout 21st century skills relevant with critical thinking, creativity, communication and digital literacy (Flavin, 2021a). This section intends to explore the feasibility of this kind of elements in the intermediate prototype.

Media Literacy

Media literacy is used to describe the ability to interact with media by carefully considering media texts and factors that shape those texts (Scharrer and Zhou, 2022). Porter (2004) emphasises that not only media technology but also the knowledge concerning the impact of media. Understanding the routes media are performed and can influence people might be a significant elements of media literacy. This means the term media literacy refers to the attitude the audience interprets or responds to the media texts in various ways (Grisham, 2021). Therefore, enhancing media literacy skills can permit users to exactly understand the intention and attribute of media and prevent users from any negative impacts of media. This is the reason a number of researchers have argued the importance of critical thinking while defining media literacy (Porter, 2004).

Digital Literacy

Digital literacy refers to the individual's skills necessary to live, work, and learn in the current world in which communication, and access to information including messages are increasing through digital technologies such as internet platforms, mobile devices, and social media (Western Sydney (University, 2022). Flavin (2021b) specifically summarises digital literacy below:

a. Acquiring skills for independent research as a life-long learner

b. Familiarity with terms and common platforms in the digital landscape

c. Collaboration as a part of a team to solve efficiently problems

d. Adapting to new technology to remain agile and up to date

e. Teaching or explaining technologies you use for the purpose of understanding and imparting knowledge

Information Literacy

Information literacy is a term used to describe an ability that individuals can determine the extent of information they need, access information effectively, critically evaluate the needed information and its sources, integrate selected information into a knowledge base (Leaning, 2019). In addition, digital information literacy refers to the ability to recognise, access and evaluate digital resources, devices, and services in an effective way and apply them to lifelong learning (Sunarjo, 2021).

21st century skills

Based on a comprehensive review of a wide range of analytical discussions, Voogt and Roblin (2010) have defined 21st century skills as new competencies that are increasingly demanded of the existing workforce by society, and which current students need to be trained in for their future jobs and careers. This definition emphasises the importance of developing skills and competencies that are relevant to the rapidly changing demands of the labour market and emphasises the need for education to equip learners with the tools and knowledge required to succeed in the 21st century workplace.

Communication skills, including language and presentation of ideas, are a vital component of 21st century skills, which enable effective collaboration and communication as well as support problem-solving (Joynes et al., 2019). Pentury et al. (2020) has emphasised creative writing can enhance students' 21st century skills and language skills by developing their communication, critical thinking, and collaboration skills. This intermediate prototype aims to provide an immersive experience of the following elements of 21st century skills.

a.Creative writing

b.Collaboration and communication

c.Critical thinking

3.1.4.3 The feature of intermediate prototype

For each feature, the following structure is used:

Description: A brief overview of the feature.

Field Note: Personal observations or experiences related to the feature.

Related Competency Element: The specific competency the feature is intended to support.

Understanding story arc

Feature description _ In an initial step for creating an interactive storybook, learners can understand Story Arc of the pre-selected book Animal Farm by carrying out web searches and upload the original source and URL address.

Field note _ I found out the Riches to Rags Story Arc of the book Animal Farm with my children and shared opinions with them on other books with similar Story Arc such as Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde. This process could lead to intellectual curiosity about other books indicating similar storylines. In addition, my children and I aimed to decide a background story to write based on before creating our own story. Interestingly, while I was inspired by classic story arcs, my son was drawn to the story arc of the film Back to the Future in the intermediate prototype.

The related competency element _ Information literacy

Fig.10. Story Arc _ Animal Farm

Fig.11. Story Arc _ Back to the Future

Summarising and familiarising the story

Feature description _ Learners summarise the plot of the book in short sentences and upload it to the designated section that is About the Story. In addition, learners can enhance their understanding and familiarisation of the plot by utilising the education app such as Quizlet.

Field note _ My children and I compared each other's sentences after each of us had provided a one-line summary of the book Animal Farm. Unexpectedly, this process led us to modify our sentences several times in order to refine them satisfactorily. This process could be a first stage of listening to others' arguments and reflecting on my idea. My daughter (Year 13) introduced us to Quizlet, an educational app that helps students learn various school subjects in the form of quizzes, which helped us immerse ourselves in the key themes and plot of the book Animal Farm.

The related competency element _ Critical thinking, Creative writing

Fig.12. Page of About the Story

Fig.13. Quizzes page of Quizlet

GCES Vocabulary Learning

Feature description _ Learners can use education resources Vocabulary.com to identify the definition of the vocabulary they choose and also learn the relevant sentence quoted in the book Animal Farm. In the next phase, learners upload the meaning of their selected vocabulary and sentences quoted in the book Animal Farm, and finally search online an image that represent the vocabulary clearly. Learners can access free image websites for image selection such as Pixabay.com. Based on the policy of Intellectual Property (IP), it is recommended to specify the original source of the image in case of use for education (GOV.UK, 2021).

Field note _ My children preferred to browsing Pinterest.com while I accessed Google Image Search provided by Google. Google is the most-visited website around the world lots of internet users already knows and Pinterest.com serves social media service for image sharing.

The related competency element _ Learning vocabulary through digital literacy

Fig.14. Vocabulary list of Animal Farm

Fig.15. An image and quoted sentence of Animal Farm

Creating a story using vocabulary

Feature description _ Learners create their own creative stories using the vocabulary they have selected. If high level GCSE vocabulary is selected, learners can alternatively replace it with simpler synonyms or similar vocabulary to create their own story. In addition, to ensure the legitimacy of the story, learners first select the background story arc that will form the basis of their story and then write their stories accordingly.

Field note _ I was interested in classic Story Arc such as Harry Potter and Sherlock Holmes, while my children preferred superhero fiction or fantasy genre.

The related competency element _ Creative writing

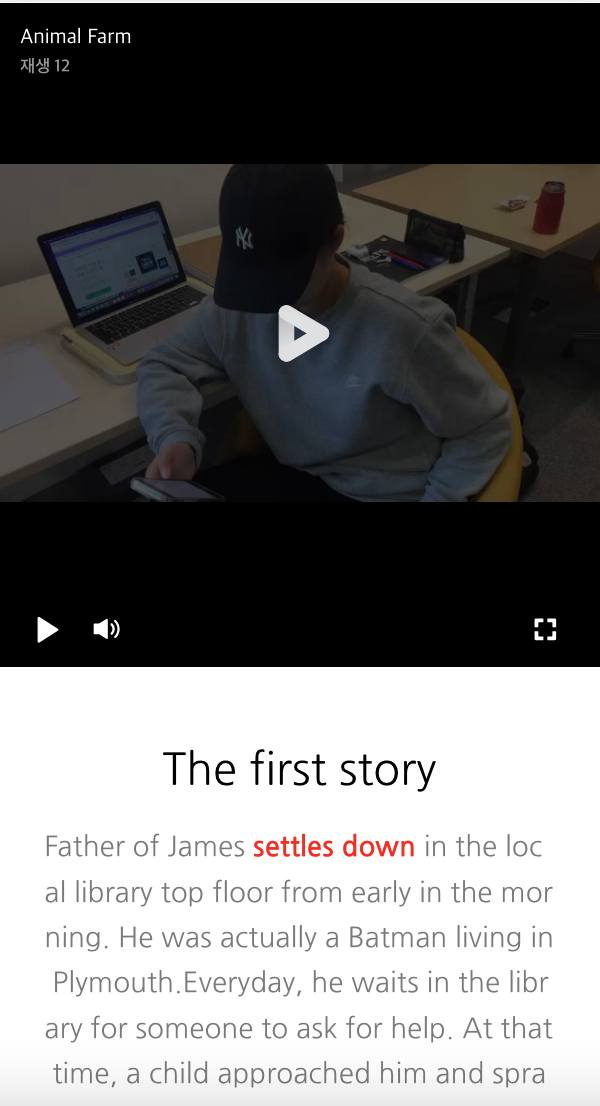

Fig.16. A story sample of my son

Creating video clip for story recording

Feature description _ As the open-source Google Blogger does not include the voice recording feature that was available in the initial prototype, learners can alternatively create a video clip using YouTube, Google's subsidiary, to record their stories and then link them to Google Blogger.

Field note _ My children used Adobe Premiere Pro to generate their scripts on video clips while recording their stories on YouTube. They intuitively learned how to use the Adobe Premiere Pro.

The related competency element _ Digital literacy

Fig.17. A video clip and her story

Searching a representative image and video clip

Feature description _ Learners searches images and video clips related to their stories through internet search. In addition, learners can use images drawn by themselves utilising graphic design tools. The source of the image they searched can be displayed at the bottom of the page, and the URL address of the original source is presented as well so that readers can immediately visit the source of the image.

Field note _ My son created a profile image that represents his YouTube account using Adobe illustrator. To achieve this, he learned basic skills by watching Adobe illustrator tutorials of YouTube.

The related competency element _ Information literacy, Digital literacy

Fig.18. A relevant image about the story

Fig.19. A video clip related to the story

Creating a linked story

Feature description _ Learners can upload their stories from the Google Blogger comment section, which is a form of engagement. This comment section is a common method of communication on social media networks and helps learners to use their mobile devices to record their stories and communicate with other learners without the constraints of time and place.

Field note _ My children re-read and modified their stories they wrote several times a day to reflect their new ideas. In this process, they desired to receive positive feedback for their new ideas after asking family members for advice. My children and I shared opinions on spelling or grammatical errors and if we did not reach satisfactory agreement, we could achieve a general consensus through Google search.

The related competency element _ Cooperation, Critical thinking

Fig.20. Writing storylines using comment section

3.1.4.4 Refining the narrative: The iterative design strategy

This study created the initial prototype to identify the potential of creative writing combined with multimedia elements based on traditional storytelling. In the second phase, in order to share these digital storytelling skills with educational researchers and teachers and to get their feedback, an intermediate prototype was created using Google Blogger, one of Google's open sources. The opinions of the participants will be collected through Delphi surveys in terms of academic expertise and the online focus group study from the perspective of field inspiration with the secondary school teachers, this will follow the research method of iterative design process as part of the evolutionary development model to explore a feasibility of an interactive storybook, and their opinions will be reflected in a final prototype (Goodman et al., 2012).

3.1.4.5 Voices from the field: User feedback and its impact on design

During the development of the intermediate prototype, feedback was actively sought in order to refine its features and functionality. Among the early respondents were my children, who had already co-authored the pilot prototype. Their unique perspective, combined with their first-hand experience, provided some invaluable insights. This initial feedback provided the basis for preparing for formal feedback from educational researchers and English literature teachers in the UK (Nielsen, 2012, Rubin and Chisnell, 2008). While the feedback was useful, it's important to note two primary limitations (Baxter and Jack, 2008):

1. Informal discussions: All feedback was received through unstructured, informal discussions. The lack of a structured feedback mechanism may have influenced the depth and breadth of the feedback received.

2. Limited expertise: Feedback was mainly from acquaintances, which may not have provided a comprehensive view of the prototype's potential. The lack of diverse expert opinion, particularly from professionals in the fields of digital storytelling and education, is a limitation in the feedback process.

Key feedback points include (Alexander, 2017, Ohler, 2013)

1. Ease of use: Several users found the prototype intuitive and emphasised its user-friendly design.

2. Feature set: The integration of media literacy tools and digital elements was often mentioned.

3. Areas for enhancement: Some users expressed that certain parts of the interface could be more intuitive. There were also suggestions for enhanced multimedia features and more comprehensive tutorials for first-time users.

3.1.4.6 Storytelling challenges: Overcoming prototype limitations

The intermediate prototype, while demonstrating potential, encountered several challenges and limitations:

a. Scalability and lack of updates in Google Blog (Armbrust et al., 2010, Cusumano, 2010):

Google Blog has not been upgraded with recent updates or features, such as integration with the latest AI capabilities. Its stagnation indicates that if Google doesn't strategically support this software, it may face limitations in scalability and adaptability to modern technological trends.

b. Integration challenges (Motro and Anokhin, 2006):

When trying to accommodate third-party tools, the prototype sometimes faced integration inconsistencies.

c. User interface consistency (Nielsen and Molich, 1990, Shneiderman et al., 2016):

Delivering a consistent user experience across devices and screen sizes was consistently challenging.

These limitations not only provide insight into areas for further refinement, but also suggest potential directions for future research and development.

3.1.4.7 Beyond the prototype: Exploring the vision for the future of digital storytelling

Based on the insights gained from user feedback and the ongoing research, the potential future enhancements to the prototype are identified:

a. Advanced multimedia features (Fisher and Baird, 2006):

The following design iterations will focus on the integration of more advanced multimedia tools. This will enable users to incorporate video, animation and other interactive elements easily into a story.

b. Collaborative tools (Dillenbourg, 1999):

The plan is to provide personalised spaces for co-authors, facilitating their active participation and supporting a more collaborative storytelling environment.

c. Incorporate cutting-edge technologies (Craig, 2013, Russell and Norvig, 2010, Milgram and Kishino, 1994):

To keep pace with the rapidly evolving technological landscape, the possibility of incorporating engaging elements such as AI and AR into the platform is constantly being explored. This will not only enhance the storytelling experience, but also keep the platform modern and engaging.

These outlined directions aim to make the platform more dynamic, interactive and user-centric, adapting to the evolving needs of our user base.

3.1.4.8 Behind the scenes: Technical basis of the interactive storybook

The intermediate prototype was strategically developed using Google Blogger, an open-source software provided by Google. This decision was based on several key considerations:

a. User accessibility (Kukulska-Hulme, 2012, Seale, 2013):

By using Google Blogger, the prototype minimised initial barriers to entry, such as login processes, and increased user accessibility.

b. Backend constraints (Boyd and Ellison, 2007):

The use of Google Blogger limited backend development and customisation. The platform had to be designed to work within the limitations of Google Blogger.

c. Maximise usage (Anderson, 2008):

The development process focused on fully exploiting the features and capabilities of Google Blogger to create a comprehensive and functional prototype.

While the choice of Google Blogger streamlined development and improved user accessibility, it also imposed certain limitations, particularly in terms of back-end customisation and advanced feature integration. However, its wide acceptance and familiarity among users made it a suitable choice for this stage of the prototype.