Refining a pilot prototype of the interactive storybook for language learning: Informed by (the first) feedback from educators and researchers

- BJ

- 2024년 7월 14일

- 77분 분량

1. Introduction

1.1 Background to the study

The area of education is undergoing substaintial change, particularly with the integration of digital technologies into learning environments. This study focuses on Educational Digital Storytelling (EDS) as a resource for enhancing the language skills of Key Stage 3 (KS3) students. EDS, an emerging pedagogical approach, combines storytelling skills with digital media to provide an engaging and interactive way to support their learning (Moradi and Chen, 2019). The study was inspired by the growing challenge of integrating traditional learning approaches with the evolving digital landscape, particularly in the context of English literature.

1.1.1 The transformation of education through digital technologies:

Recent literature has emphasised the rapid evolution of digital tools in education, focusing on their transformative impact on pedagogical methods (Wang, 2023). These developments require an exploration of how these technologies can enhance the educational experience, particularly in language learning. EDS, as noted by Bryant et al. (2020), integrates storytelling techniques with digital environments and provides a convincing approach to engage learners more closely in the learning process (Akbar, 2016).

1.1.2 Digital literacy in contemporary curricula:

The emerging emphasis on digital literacy in contemporary curricula, as outlined by Blue (2022), is consistent with the aims of this study. She argues that digital literacy is not just an additional skill, but a critical elements of a comprehensive 21st century education. In the specific context of English literature, the integration of digital storytelling techniques can transform traditional pedagogy and make learning more relevant and accessible to the current generation of learners (Bandura and Leal, 2022, Wu and Chen, 2020).

1.1.3 Insights into digital teaching methods:

Comparative studies by Vas (2023) have demonstrated that digital learning methods can provide advantages over traditional approaches, particularly in supporting student engagement and motivation in language learning (Learning, 2023). However, these methods also present specific challenges, such as the necessity for teacher training and the adaptation of existing curricula to effectively reflect digital elements (Røe et al., 2022).

1.1.4 Adapting education to technological evolution:

Acknowledging the importance of adapting to technological advances, researchers such as Winthrop et al. (2016) emphasise the importance of education systems continuously evolving. They suggest that incorporating digital tools into teaching and learning strategies can help to enhance learner outcomes, particularly in terms of language and literacy development (Nguyen, 2023, Cruz, 2023).

1.1.5 Understanding the learning contexts of KS3 students:

1.1.5 Understanding the learning contexts of KS3 students:

It is important to understand the specific learning contexts of KS3 students. Martin’s (2021) and Hayter's (2022) research on this age group indicates a marked tendency towards interactive and multimedia-based learning, which further supports the relevance of this study to the language education of KS3 students. This is in line with the findings of Smeda et al. (2014) who emphasise the effectiveness of digital storytelling in engaging younger learners.

1.1.6 Aim of the study:

By integrating these perspectives, this study aims to explore the potential of EDS to enhance the language skills of KS3 students, situating its investigation within a broader educational and technological context. The study aims to contribute to the growing body of research on the application of digital storytelling in language education (Chan et al., 2017, Moradi and Chen, 2019).

1.2 Aims and objectives of the research

The primary aim of this research is to investigate and enhance the language skills of Key Stage 3 (KS3) students in the environment of Educational Digital Storytelling (EDS). This study aims to bridge theoretical insights with practical applications in a digital learning environment, based on the importance of incorporating expert opinion and educator contributions in the development and implementation of educational technologies (Eshbayev and Nasiba, 2023, Kafyulilo et al., 2015). The specific aims of the research are

1.2.1 Analyse feedback from UK researchers

To analyse feedback from the researchers on the key competences identified in a preliminary literature review for enhancing language skills in the EDS environment. This analysis will inform the theoretical basis for the development of the pilot prototype, the Interactive Storybook, making sure that it is based on pedagogical principles and practices (Scanlon et al., 2019). Incorporating expert opinion into the design and evaluation of educational technology is important for its effectiveness and relevance (Kali and Fuhrmann, 2011).

1.2.2 Evaluating feedback from secondary school teachers

To evaluate and analyse feedback from secondary school teachers in England on the potential feasibility of the Interactive Storybook in school environments. This objective aims to establish that the pilot prototype is not only theoretically effective, but also practically feasible and relevant in real educational contexts, bridging the gap between theory and practice (Çoklar and Yurdakul, 2017). The contribution of educators plays a key role in the successful integration of educational technologies in secondary schools (Spiteri and Chang Rundgren, 2020).

1.2.3 Understanding the impact of the extended prototype

To understand how the enhancements made to the Interactive Storybook, based on the first round of feedback from researchers and secondary school teachers, can effectively improve the language skills of KS3 students in an EDS environment. This will involve evaluating the practical implementation and pedagogical impact of the refined Interactive Storybook, with a focus on its potential to enhance language learning experiences and outcomes (Swan et al., 2014). Iterative design and feedback-based improvement are important for the effectiveness of educational technology (Sailer et al., 2021).

These aims are designed to provide a comprehensive approach to the study, considering both the theoretical aspects of EDS and the practical challenges of implementing digital storytelling tools in educational contexts. The research aims to contribute to the area of educational technology by providing insights into the effective integration of digital storytelling in language learning, particularly for KS3 students, while emphasising the importance of interdisciplinary approaches to educational technology research (Scanlon et al., 2019).

1.3 Overview of Educational Digital Storytelling (EDS)

1.3.1 Definition of Educational Digital Storytelling (EDS)

Educational Digital Storytelling (EDS) is the convergence of storytelling techniques and digital media to create immersive and interactive learning experiences. Compared to traditional pedagogies, EDS positions learners as active participants in the storytelling process rather than passive recipients of information (Meletiadou, 2022, Robin, 2008). This approach uses a range of digital tools such as interactive storybooks, digital animations and multimedia presentations to make learning more engaging and personal (Yuksel-Arslan et al., 2016).

1.3.2 Benefits and skills enhanced by EDS

Researchers have recognised EDS as an influential approach for improving a range of skills, including digital literacy, creative thinking and language skills (Meletiadou, 2022, Niemi and Multisilta, 2016). The interactive and participatory aspects of EDS have been demonstrated to facilitate in-depth involvement with content, promoting not only knowledge acquisition, but also critical thinking and creativity (Smeda et al., 2014, Yang and Wu, 2012).

1.3.3 Empirical evidence for EDS

Research in the area of digital storytelling, such as Ranieri and Bruni's (2018) study on media literacy in teacher education and Smeda et al.'s (2014) comprehensive study on its effectiveness in the classroom, provides empirical evidence to support the use of EDS in enhancing student engagement, creativity and digital literacy skills. In addition, a meta-analysis by Wu and Chen (2020) emphasises the positive effects of digital storytelling on learner outcomes and motivation.

1.3.4 Practical applications of EDS

A classroom application of EDS might involve students collaboratively creating digital stories that incorporate multimedia elements, enhancing their language skills and digital literacy (Alismail, 2015, Rizvic et al., 2019). Such practical applications illustrate how EDS can transform traditional classroom environments into more active and interactive learning environments (Robin, 2008).

1.3.5 Pedagogical Rationale for EDS

The pedagogical basis for EDS is consistent with contemporary educational theories that emphasise the value of involving students in their learning. For instance, constructivist learning theory supports the EDS approach by emphasising the role of students in constructing their own knowledge through interactive and practical experiences (Abderrahim and Gutiérrez-Colón Plana, 2021, Mattar, 2018). Social constructivism also supports EDS as it encourages collaboration and knowledge sharing between learners (Kimmerle et al., 2015).

1.3.6 Transforming learning through EDS

By embedding educational content in immersive stories and using interactive digital formats, EDS aims to transform learning into a conversational and experiential process, which can lead to improved understanding and retention of learned content (Thompson, 2000, Zwart et al., 2017). This methodology is in line with contemporary educational frameworks that emphasise the importance of student engagement and active learning in effective teaching (Schugar et al., 2013, Zainuddin et al., 2019).

2 Survey methodology

2.1 Survey design

The methodology used in this study involved the design and administration of two different surveys, each targeting a different group of participants and focusing on specific aspects of Educational Digital Storytelling (EDS). The use of multiple surveys is in line with the recommendations of (Creswell and Creswell, 2017), who suggest that the use of different data collection methods can provide a more comprehensive understanding of the research problem.

2.1.1 Survey for educational researchers

The first survey, aimed at educational researchers in the UK with expertise in digital storytelling and creative education, focused on identifying the key competencies required to enhance language skills in the EDS environment. This focus was based on the desire for expert views and feedback on the competencies required to enhance language skills in the EDS context. A Delphi (online) survey method, similar to the approach described by Linstone and Turoff (2002), was used for this group. This method facilitated the collection of consensus-based evidence from researchers in different areas of the UK, securing a comprehensive and systematic approach to capturing expert insights in educational research (Hsu and Sandford, 2007).

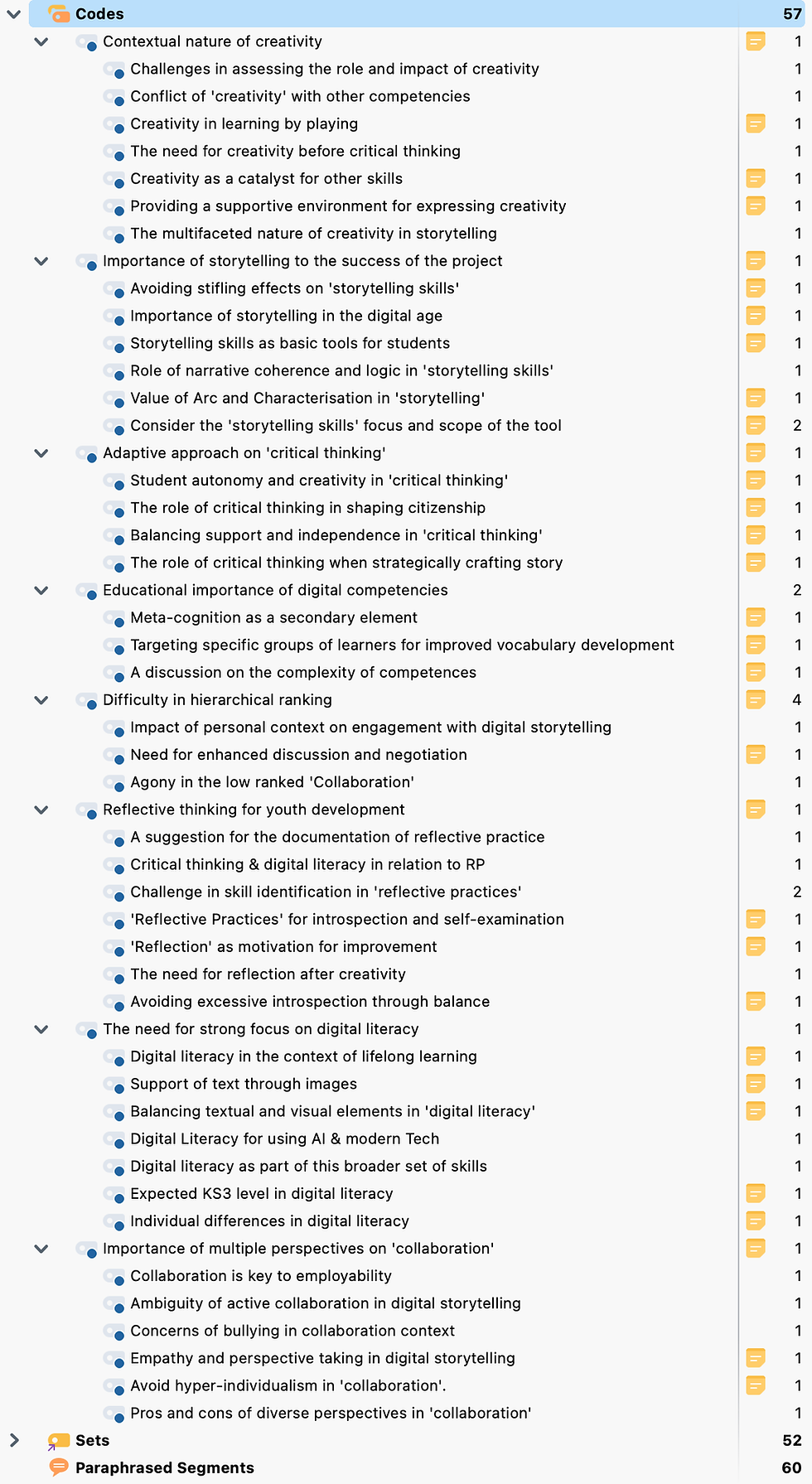

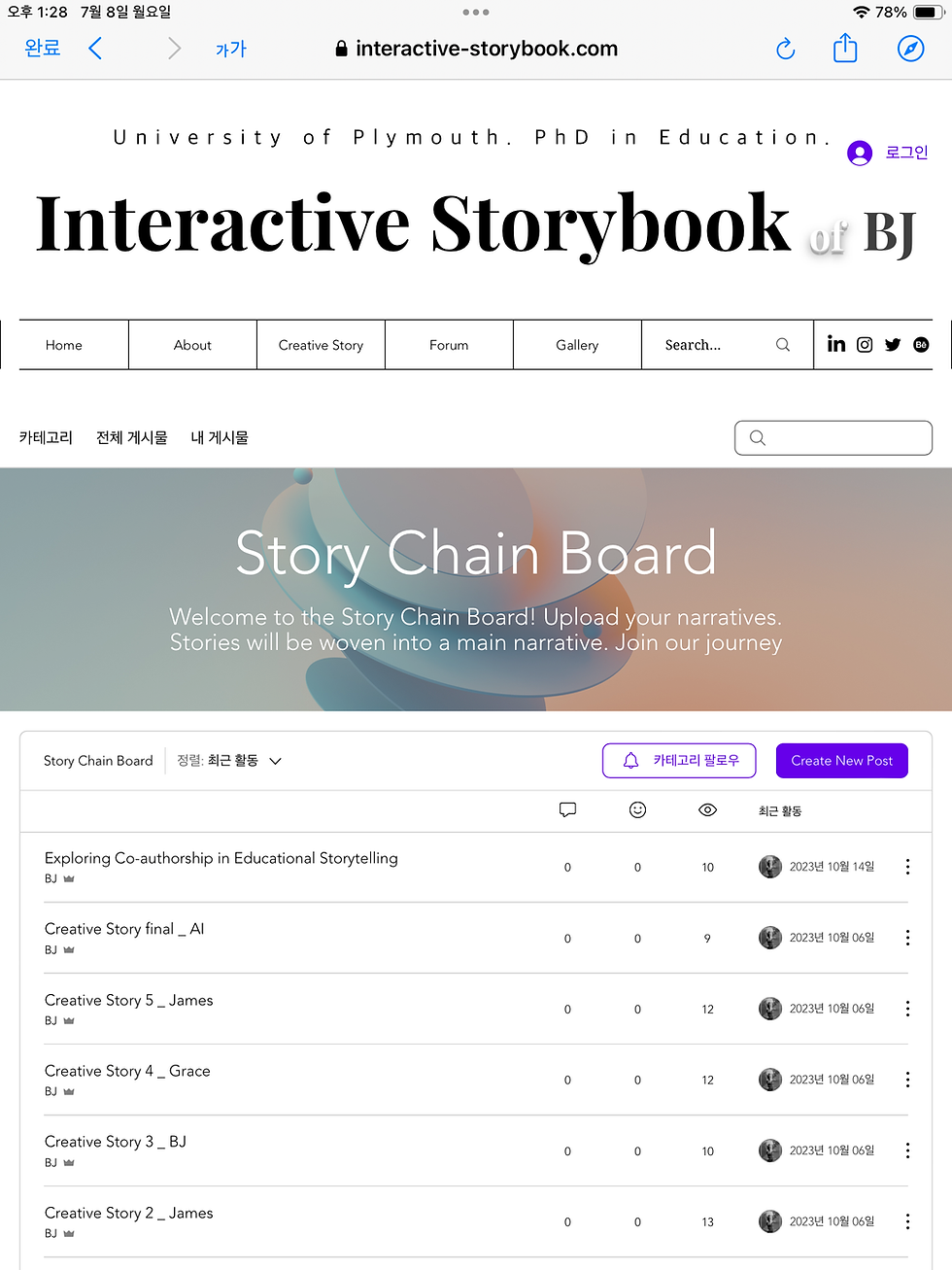

Figure 1 illustrates the process of qualitative data analysis using MAXQDA software, a widely recognised tool for computer-assisted qualitative data analysis (Kuckartz and Rädiker, 2019). This screenshot demonstrates the coding of the researchers' responses to the question about the ranking of competencies in Educational Digital Storytelling (EDS). The left panel represents the hierarchical coding system, while the main panel represents the coded segments of a participant's response, in line with best practices in qualitative data analysis (Saldaña, 2021). This visual representation demonstrates the rigorous approach to data analysis, emphasising key themes such as the relative importance of metacognition and the presumed digital literacy skills of KS3 students. Such detailed analysis provides a comprehensive understanding of experts' perspectives on the competencies required for the development of language skills in EDS environments, contributing to the trustworthiness and credibility of the research findings (Lincoln and Guba, 1985).

<Fig.1: Qualitative data analysis of researcher feedback using MAXQDA>

2.1.2 Survey of secondary school teachers

In contrast, the other survey was aimed at secondary school teachers in England and focused on exploring the feasibility of implementing the Interactive Storybook, the pilot prototype of this study, in real classroom environments. This survey aimed to collect practical feedback on the usability, engagement and integration potential of the prototype within the school curriculum. An online survey methodology, as discussed by Dillman et al. (2014) in their exploration of online surveys as a viable option in educational research, was used to efficiently collect and analyse feedback from teachers in different locations across England. Their study emphasises the practicality and effectiveness of online surveys in educational contexts, particularly for collecting diverse perspectives from geographically dispersed participants.

Figure 2 illustrates the process of qualitative data analysis of school teachers' feedback using MAXQDA software, a tool for qualitative data analysis (Kuckartz and Rädiker, 2019). This screenshot illustrates the coding of schoolteacher responses regarding the usability and engagement of the pilot interactive storybook. The left panel illustrates the hierarchical coding system, while the main panel indicates the coded segments of a participant's response, following best practices in qualitative data analysis (Saldaña, 2021). The coding process reveals key themes such as ease of navigation, engagement through multimedia elements, and potential concerns about distraction. This systematic approach to data analysis enhances the credibility and trustworthiness of the research findings (Lincoln and Guba, 1985) and provides insights into the practical implementation of the Interactive Storybook in the classroom.

<Fig. 2: Qualitative analysis of school teachers' feedback using MAXQDA>

2.2 Methodological considerations and analysis process

This study employed a mixed methods approach, combining quantitative ranking data with qualitative thematic analysis (Creswell and Clark, 2017). The methodology integrated feedback from both theoretical and practical perspectives, providing evidence to support the findings of the study. This approach is consistent with Ivankova and Plano Clark's (2018) emphasis on the integration of multiple perspectives in mixed methods research.

The study used different, but complementary, survey approaches to gain insights into the effective use of EDS to enhance language learning. The structure and approach of these surveys were informed by the British Educational Research Association’s (2019) guidelines and best practices for educational research, which emphasise the importance of targeted surveys in educational contexts.

For the qualitative data analysis, thematic analysis was employed using MAXQDA software (Kuckartz and Rädiker, 2019). The coding process involved first coding a subset of the data, followed by discussions between the researchers involved to resolve discrepancies and reach consensus. This approach increases the reliability and validity of the coding process (Saldaña, 2021).

Figure 4 illustrates the iterative design process used in the development of the interactive storybook for language learning. This methodology integrates multiple stakeholder perspectives through a series of feedback cycles (Amiel and Reeves, 2008). The process began with a Delphi survey of researchers, followed by the creation of an initial prototype. This prototype was then refined through a second Delphi survey of researchers and an online survey of teachers, resulting in Prototype Edition 2. The final iteration incorporated feedback from EdTech professionals, resulting in Prototype Edition 3.

This approach is consistent with design-based research principles in educational technology, which emphasise the importance of iterative development and stakeholder engagement (McKenney, 2018b). The involvement of both academic experts (researchers) and field experts (school teachers and EdTech professionals) provided a comprehensive evaluation that balanced theory and practice (Hall, 2020).

By providing this detailed account of our methodological process, we aim to enhance the replicability and credibility of the study and provide a more thorough understanding of our research approach and findings.

<Fig. 3: Iterative design process for interactive storybook evolution>

2.3 Survey focus and rationale

2.3.1 Focus of the Educational Researcher Survey

The initial survey was aimed at educational researchers with expertise in digital storytelling and creative education. Based on the conceptual framework proposed by Robin (2008), which emphasises the multifaceted aspects of digital storytelling in educational contexts, the survey focused on identifying and defining key competences required for KS3 students in educational digital storytelling (EDS) environments. This is in line with the methodology proposed by Sarica and Usluel (2016), which involves subject experts in the identification of key educational competencies.

2.3.2 Identification and ranking of competences

Participants were provided with a list of potential competencies and their respective sub-elements, which were derived from a systematic literature review titled "Exploring anticipated competency elements for enhancing language skills of KS3 students in an educational digital storytelling environment" conducted prior to this study. These competencies were developed based on the educational framework proposed by van Laar et al. (2017), which highlights the importance of different skill competencies in a modern educational framework. Respondents were then required to rank these competencies according to their perceived importance in enhancing the language skills of KS3 students. This method is supported by the findings of Burkle and Cobo (2018), who emphasise the value of expert insight in educational research.

2.3.3 Focus of the survey of secondary school teachers

The following survey was designed for secondary school teachers in England and focused on the practical use of the EDS pilot prototype, the Interactive Storybook. This approach is in line with the recommendations of Nind et al. (2016), who emphasise the importance of teacher feedback in education. The aim of the survey was to collect comprehensive feedback on different aspects of the Storybook, including usability, engagement and potential for curriculum integration. This methodological approach is supported by the findings of Mandinach and Jimerson (2016) on the evaluation of educational technology in the classroom.

2.4 Theoretical and practical frameworks

2.4.1 The importance of usability and engagement

The success of digital learning tools is closely influenced by their usability and ability to engage learners, as research and discussion in the area has emphasised. Research by Bourgonjon et al. (2010) demonstrates the potential of digital learning tools to support student engagement and success, suggesting that these tools can substantially transform teaching and learning methods. In addition, a systematic review by Bond et al. (2020) reveals a complex landscape of student engagement with digital technologies, emphasising the multiple dimensions and definitions of participation, such as behavioural, social and cognitive aspects.

2.4.2 Curriculum integration with the TPACK framework

In addition, the aspect of curriculum integration potential is based on the TPACK framework introduced by Mishra and Koehler (2006). This framework discusses the integration of emerging educational technologies into existing curricula through a balanced interplay of content knowledge, pedagogical knowledge and technological knowledge. The TPACK framework emphasises that effective technology integration in education is not just about the technology itself, but how it is cohesively integrated with pedagogical methods and content understanding (Harris et al., 2009).

2.5 Evaluating feasibility and effectiveness

2.5.1 Importance of practical evaluation

It was also considered important to evaluate the feasibility of the Interactive Storybook in real educational environments. This aspect of the research was informed by the principles emphasised by McKenney (2018a), which focus on the importance of evaluating educational technologies in the context of their practical application in authentic learning environments. Such evaluations focus on the real-time adaptability of technology to student demands and the generation of both research and practice-based knowledge for effective technology integration (Plomp, 2013).

2.5.2 Collecting detailed feedback

Both surveys included open-ended questions to collect detailed feedback and reflections on the EDS environment and the Interactive Storybook. The inclusion of open-ended questions is in line with the recommendations of Cohen (2002), who suggest that such questions can provide abundant, qualitative data that can provide in-depth insights into participants' perceptions and experiences.

2.6 Profile of participants (researchers and secondary school teachers)

2.6.1 Educational researchers

Selection criteria:

Participants in the initial survey were carefully selected using criteria based on established research methodologies. As emphasised by Yuksel et al. (2011), the expertise of participants in areas such as digital storytelling, creative education and curriculum development is important for collecting informed and challenging feedback. The group included educational researchers from a range of academic institutions, a decision supported by Tight’s (2018) findings on the value of diverse academic perspectives in educational research. To further refine the selection criteria for educational researchers to participate, specific qualifications were considered, such as years of experience in education, published research in the area, and active involvement in curriculum development. This approach provided a wide range of insights and contributed to a sophisticated understanding of digital storytelling in education, in line with Creswell’s (2015) recommendations for purposive sampling in qualitative research.

Relevance of research findings:

The research findings of Curry (2021) and Cao et al. (2023) were particularly relevant to the discussion of findings on digital education and language learning. For instance, Curry’s (2021) study provides insights into how digital storytelling can enhance language comprehension, while Cao et al. (2023)'s (2021) study emphasises the adaptability of digital tools in different language learning contexts. These studies emphasise the importance of EDS in enhancing language learning, reinforcing the relevance of the research conducted by education experts in this study.

2.6.2 Secondary school teachers

2.6.2.1 Importance of practical experience:

The following survey was conducted with secondary school teachers in England, a selection based on established principles of educational research. The importance of the practical experience of teachers in educational research is widely recognised. Gore and Gitlin (2004) emphasise the importance of involving teachers in educational research as their insights can contribute substantially to the legitimacy and authority of the profession and its knowledge base. In addition, the role of teachers in engaging with educational research is emphasised, where projects that are meaningful to teachers and a supportive culture of research engagement are necessary for positive outcomes (Cain, 2015). This is particularly important for tools such as the Interactive Storybook, which are designed for direct use in the classroom.

2.6.2.2 Classroom insights and integration:

These participants were selected for their classroom involvement and practical experience with the secondary age group. As emphasised by Rienties and Kinchin (2014), teachers' perspectives are key in assessing how closely new educational tools reflect the demands and dynamics of specific student age groups. This view is supported by Mercer et al.'s (2019) insights into the importance of social learning in the use of digital tools. Social learning in this context refers to the process by which students learn from each other through collaboration, interaction and shared experiences, which is important in a digitally-focused educational environment (Greenhow et al. (2019). It emphasises the role of peer-to-peer engagement and shared learning experiences in enhancing the effectiveness of digital tools in education. In addition, the findings of Hargreaves and O'Connor (2018) support the idea that teachers, through their daily interactions with students and their accumulated experiences, provide critical insights into the engagement and usability of educational technologies in real classroom environments.

Their contributions were valuable in understanding how Educational Digital Storytelling (EDS) tools, such as the Interactive Storybook, could be integrated into existing teaching methods and curricula. Robin (2008) emphasises the importance of such integration for the successful use of new educational technologies, emphasising the importance of feedback from educators who are actively involved in the educational process. This feedback is key to understanding how the Interactive Storybook can facilitate a more social and collaborative learning environment, encouraging students to interact not only with the content but also with each other, enhancing the overall learning experience.

2.6.3 Balanced perspective

The selection and involvement of both educational researchers and educators in this study provided a balanced perspective, combining theoretical knowledge with practical classroom insights. This approach was important in keeping the findings of the study both academically grounded and practically relevant, making a meaningful contribution to the area of educational digital storytelling. The integration of different perspectives is in line with Onwuegbuzie and Leech’s (2005) recommendations for increasing the validity and reliability of qualitative research through triangulation.

2.7 Data collection and analysis process

2.7.1 Data collection timeframe and methodology

Data collection for this study was conducted over more than a six-month period, a duration determined based on proven practices in educational research, including data curation and analysis, as emphasised by Louis Cohen and Morrison (2007). This timeframe was considered acceptable for the completion of both surveys and the collection of a comprehensive dataset of responses. The data collection methodology was designed to secure the quality and reliability of the data, following the guidelines provided by Creswell and Creswell (2017) for conducting survey research in education.

2.7.2 Challenges in selecting and adapting the survey tool

Initially, the JISC online survey tool was used to design the surveys. However, in the autumn of 2023, the JISC online survey underwent a significant update that resulted in a substantial limitation in its features. The changes made it impossible to implement the original survey design as planned. As a result, the researcher used the 'Survey and Poll' tool as an alternative. This tool, designed to be easily integrated into web platforms, was embedded into the main research project website, where the pilot prototype was deployed. Switching to the 'Survey and Poll' tool was instrumental in maintaining the integrity of the survey design and providing efficient participant engagement. This method is in line with current methodological trends in research that prioritise accessibility and convenience for participants, a facilitating element that is increasingly recognised as a facilitator of participation, as demonstrated by Couper (2017) and Heerwegh (2009).

2.7.3 Thematic coding approach to data analysis

A thematic coding approach was used in data analysis to identify, analyse and interpret meaningful units within the data and organise them into coherent themes. This method, described in detail by Braun and Clarke (2021) and Kiger and Varpio (2020), involves a systematic yet flexible process of moving from data to ideas through creative coding. It is a widely used technique in qualitative research and is known for its effectiveness in identifying patterns and themes in complex datasets.

2.7.3.1 Systematic but flexible process

This approach is consistent with the concepts discussed by Braun and Clarke (2021), who detail the process of thematic analysis and outline its systematic approach while maintaining flexibility. In addition, Kiger and Varpio (2020) elaborate on the process of coding in thematic analysis, emphasising its role as a creative link between data collection and analysis and its importance in moving from data to ideas.

2.7.4 Coding process and theme generation

Initial codes were generated based on the key competencies and feedback sections mentioned in the surveys, following the coding procedures outlined by Elliott (2018). These codes were then carefully refined and organised into key themes. This process facilitated a comprehensive and sophisticated analysis of the feedback, providing a more in-depth understanding of participants' perspectives and insights, in line with the principles of reflexive thematic analysis outlined by Clark and Braun (2021) and Braun et al. (2023). Throughout the coding process, ongoing feedback was sought from the researcher's supervisor and peer group. This collaborative approach provided validity and reliability to the thematic analysis, identified potential biases and refined the initial codes into key themes, following Elliott's (2018) coding procedures.

Figure 3 illustrates a hierarchical coding structure resulting from the thematic analysis of feedback from UK researchers on digital storytelling skills (Braun and Clarke, 2006). The coding framework represents major themes (parent codes) and their associated sub-themes (child codes), providing a comprehensive overview of the key areas of focus identified in the study (Saldaña, 2021). This visual image demonstrates the multifaceted perspective of the researchers, encompassing aspects such as creativity, storytelling, critical thinking, digital literacy and collaboration (Robin, 2008, Niemi et al., 2018). The hierarchical structure facilitates a sophisticated understanding of the interrelationships between different competencies and their perceived importance in the context of digital storytelling education (Lambert and Hessler, 2018, Wu and Chen, 2020).

<Fig.4: Thematic analysis of feedback from UK researchers on digital storytelling skills>

Figure 4 illustrates the key themes identified from a thematic analysis of feedback provided by English school teachers on an interactive storybook tool. This coding framework represents the main areas of concern and interest indicated by educators in their evaluation of the tool (Braun and Clarke, 2019). The themes range from positive responses and user experience concerns, to potential applications in educational contexts and resource limitations. This structure provides valuable insights into the multifaceted perspectives of field educators on the integration of digital storytelling tools in classroom environments (Ertmer et al., 2012). The frequency counts associated with each theme provide a quantitative dimension to the qualitative data, providing a sophisticated understanding of the relative prominence of different aspects in educator feedback (Creswell and Clark, 2017). This analysis provides an important basis for refining the tool and developing implementation strategies that are responsive to the requirements and concerns of educators in the English school system (Burden and Kearney, 2017).

< Fig.5: Thematic analysis of English school teachers' feedback on an interactive storybook tool

2.7.5 Focus of analysis

The analysis of the collected data was carefully designed to identify patterns and trends in the responses, a key step in educational research. This focus is in line with the methods discussed by Cohen et al. (2002) who emphasise the importance of collecting practical insights from educators in order to meaningfully evaluate the impact of educational interventions. The use of thematic analysis in this study was imperative as it is a widely accepted technique for analysing complex qualitative data, as described by Braun and Clarke (2021).

2.7.5.1 Key areas of analysis and findings

This method facilitated a detailed exploration of potential areas for improvement in the interactive storybook. It also facilitated the identification of key elements that influence the potential effectiveness of Educational Digital Storytelling (EDS) in language learning. This approach is consistent with recent studies, such as those by Indriani and Suteja (2023) and Nikbakht and Neysani (2023), which emphasise the importance of digital storytelling in developing language skills, digital literacy and critical thinking in young and EFL learners. Such a comprehensive approach provides a broader perspective on the elements that contribute to the success of digital learning tools in educational environments.

2.7.6 Summary of the methodological approach

The methodology included both electronic data collection for efficiency and in-depth thematic analysis to provide insights into the effectiveness and potential for improvement of the Interactive Storybook and EDS tools in language learning. This approach is in line with Creswell and Creswell's (2017) recommendations for conducting mixed methods research in education.

3.Initial feedback and analysis of researchers and educators

3.1 Feedback of researchers

3.1.1 Results of the ranking task

The Delphi study conducted in the first round aimed to define the key competencies required for KS3 students in an Educational Digital Storytelling (EDS) environment. Invitation emails were sent to 54 academic experts in digital storytelling and education in the UK, and responses were received from 8 participants. This response rate is in line with typical Delphi studies, which often have a response rate of less than 10% (Hsu and Sandford, 2007).

The ranking task involved academic experts ranking the competencies identified in a preliminary survey. The rankings were then converted into scores, with the most important competency receiving 6 points, the second most important competency 5 points, and so on, with the least important competency receiving 1 point. The final rankings were determined on the basis of the total scores for each competency. The results of the ranking exercise are as follows

Storytelling skills (33 points)

Creativity (32 points)

Digital literacy (27 points)

Critical thinking (26 points)

Collaboration (25 points)

Reflective practice (25 points)

Although storytelling skills ranked first and creativity a close second, it is notable that the overall distribution of scores was relatively even across all competencies. This suggests that all identified competencies are considered important for KS3 students in an EDS environment, which is in line with the findings of previous studies emphasising the importance of various skills in digital storytelling (Robin, 2008, Niemi and Multisilta, 2016, Ohler, 2013).

The even distribution of scores also reinforces the interconnectedness of these competencies, as discussed by Falloon (2020), who emphasised the importance of combining different digital literacies to enhance educators' effectiveness in higher education contexts. This comprehensive approach to skills development is further supported by Wang et al. (2020b) who demonstrated the critical role of digital literacy in students' academic success and overall satisfaction during the pandemic.

<Fig.6: Ranking of key competences for KS3 students in the EDS context>

3.1.2 Analysis of coding results

The coding analysis of the researchers' opinions provided valuable insights into the competencies required for KS3 students in an Educational Digital Storytelling (EDS) environment. The main codes identified various aspects of each competency, emphasising its importance, challenges and relationships with other competencies.

Creativity:

In relation to creativity, the analysis identified its contextual features and the challenges in assessing its role and impact. The importance for a supportive environment to express creativity and its potential to act as a catalyst for other competences was also identified (Cremin et al., 2018). The multifaceted aspect of creativity in storytelling was also identified, in line with the findings of Ohler (2013) who discussed the importance of creativity in digital storytelling.

The thematic network analysis (Figure 6) visually represents the multifaceted nature of creativity in EDS, aligning with Glăveanu’s (2018) sociocultural perspective on creativity in education. This analysis reveals the complex interplay between creativity and other competencies, as well as the importance of environmental factors in fostering creative expression (Beghetto, 2019).

<Fig.7: Thematic network analysis of creativity in educational digital storytelling>

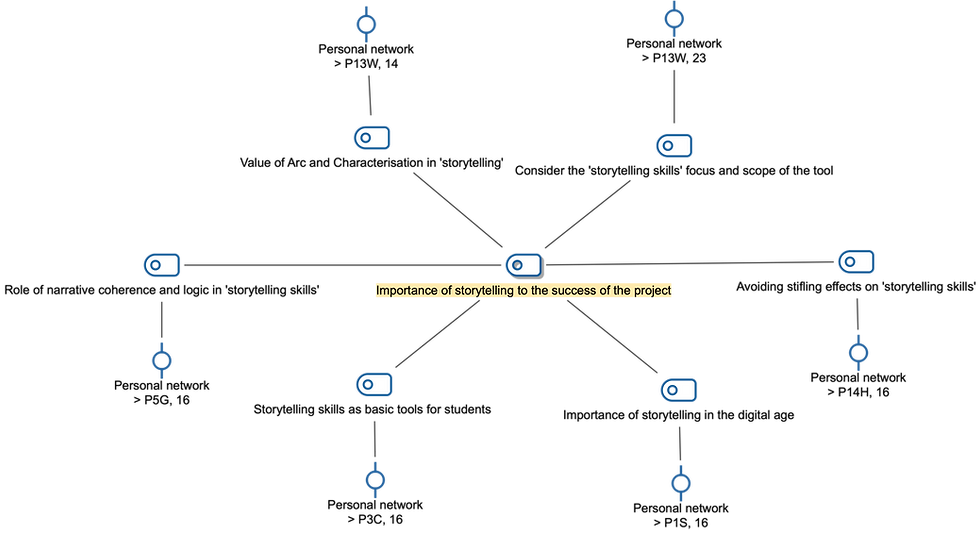

Storytelling skills:

The thematic network analysis (Figure 7) reveals the key importance of storytelling skills to the success of the project. The researchers emphasised the importance of avoiding stifling effects on these skills, in line with the findings of Niemi et al. (2018) on the value of creative freedom in digital storytelling. The analysis identified key elements of effective storytelling, including narrative coherence, logic, arc and characterisation (Alexander, 2017). The coding also indicated the importance of considering the focus and scope of the tool in relation to storytelling skills, reflecting Lambert and Hessler’s (2018) emphasis on customising digital storytelling approaches to specific educational contexts. In addition, the network emphasises the perceived importance of storytelling skills as fundamental tools for students and their relevance in the digital age, supporting Rossiter and Garcia’s (2010) argument for the continuing value of narrative in education.

<Fig.8: Thematic network analysis of storytelling in educational digital storytelling>

Critical thinking:

Critical thinking plays a fundamental role in shaping citizenship and strategically crafting narratives in the digital age. Researchers have proposed an adaptive approach to critical thinking that balances support and independence (Wegerif et al., 2015). This approach recognises the importance of student independence and creativity in the development of critical thinking skills (Paul and Elder, 2019).

The role of critical thinking in shaping citizenship is particularly important in the context of digital literacy. As students navigate complex online environments, they need to develop the ability to critically evaluate information and engage in responsible digital citizenship (Renee, 2010). This aligns with the concept of strategic storytelling, where critical thinking is key to analysing and creating meaningful narratives in different media formats (Dwyer et al., 2014).

The balance between support and independence in developing critical thinking skills could be critical for educators. While guidance is required, particularly in the early stages, it is equally important to enable students to develop autonomy in their critical thinking processes (Facione, 2011). This balance can be achieved through scaffolded learning experiences that gradually reduce support as students become more proficient in applying critical thinking skills in different contexts (Gelder, 2005).

The figure 8 depicts a conceptual map illustrating the interrelated aspects of critical thinking in education. It highlights the relationships between adaptive approaches, student autonomy, citizenship education and storytelling. Personal networks are represented, suggesting the social dimension of critical thinking development.

<Fig.9: Conceptual framework for integrating critical thinking in digital age education>

The difficulty of hierarchically competencies:

The coding analysis revealed significant challenges in hierarchically ranking skills, particularly in the context of digital literacy and storytelling. This difficulty stems from the complex interaction between different skills and the influence of personal context on how individuals engage with digital media (Eshet, 2004).

The impact of personal context on engagement with digital storytelling emerged as a critical element complicating the ranking process. Individual experiences, cultural backgrounds and prior knowledge significantly influence how learners interact with and create digital narratives (Robin (Robin, 2008), 2008). This variability makes it difficult to establish a universal hierarchy of skills, as the relative importance of different skills may vary according to personal circumstances and learning environments (Jenkins et al., 2009).

To address these challenges, researchers and educators might consider adopting a more flexible and context-sensitive approach to skills assessment. This could include the development of adaptive frameworks that take into account individual differences and the specific requirements of various digital storytelling tasks (Mishra & Koehler, 2006).

The below image represents a conceptual map illustrating the complexities surrounding the hierarchical ranking of digital storytelling literacies. It emphasises the links between personal context, the challenges of collaboration, and the requirement for more discussion in the assessment of skills. The diagram emphasises the multifaceted aspects of digital literacies and the difficulties in establishing a general ranking system.

<Fig.10: Challenges in hierarchical ranking of digital storytelling skills>

Reflective practice:

Reflective practice emerged as a key element of youth development, closely linked to critical thinking and digital literacy skills. The analysis revealed that reflective practices serve multiple purposes: promoting introspection, facilitating self-examination, and motivating improvement (Schon, 1984). However, researchers emphasise the importance of a balanced approach and caution against excessive introspection, which can inhibit action and progress (Finlay, 2008).

The intersection of reflective practice with critical thinking and digital literacy is particularly noteworthy in the context of contemporary education. As young people navigate complex digital environments, the ability to critically reflect on their interactions and creations becomes increasingly important (Buckingham, 2015). This link between skills supports the development of digital citizenship and enhances learners' ability to engage thoughtfully with online content (Jenkins, 2009).

Researchers suggest that documenting reflective practice is a valuable strategy for enhancing learning and skills development. This documentation process can take various forms, from digital portfolios to reflective journals, providing tangible evidence of growth and facilitating metacognitive awareness (Moon, 2013). However, the analysis also identified challenges in identifying skills within reflective practices, suggesting a role for more structured approaches to guide learners in recognising and articulating their developing competencies (Boud et al., 2013).

The coding findings emphasise the importance of embedding reflective practice within pedagogical frameworks, particularly those focused on digital literacy and storytelling. By facilitating a culture of reflection that balances introspection with outward-looking action, educators can support comprehensive youth development that prepares learners for the complexities of the digital age (Mezirow, 1991).

The image depicts a conceptual map illustrating the multifaceted role of reflective thinking in youth development. It emphasises the links between reflective practices, critical thinking, digital literacy and personal development. The figure emphasises the balance between introspection and action, and the importance of documentation in the reflective process.

<Fig.11: The role of reflective thinking in youth development and digital literacy>

Digital literacy:

Digital literacy has emerged as a critical skill, particularly in the context of lifelong learning and the rapidly evolving technological landscape. The analysis revealed that digital literacy is not just an isolated skill, but part of a broader set of competencies required to navigate the current world (Gilster and Glister, 1997, Lankshear and Knobel, 2008).

Research emphasises the importance of digital literacy for the use of AI and current technologies, emphasising its role in preparing individuals for future challenges and opportunities (Niemi and Multisilta, 2016). This relationship reinforces the importance for education systems to continuously adapt their digital literacy curricula to keep pace with technological advances (Ala-Mutka, 2011).

A key finding is the requirement for a balance between textual and visual elements in digital literacy education. This balance reflects the multimodal aspects of digital communication and information presentation in contemporary digital environments (Kress, 2003). Supporting text with images emerged as an important aspect, suggesting that effective digital literacy instruction should incorporate different media formats to enhance comprehension and engagement (Jewitt, 2008).

The analysis also identified individual differences in levels of digital literacy, suggesting the rationale for personalised approaches to digital literacy education. This variability challenges the expectation of a single level of digital literacy at particular stages of education, such as Key Stage 3 (KS3), and suggests the importance of flexible, adaptive learning pathways (Bennett et al., 2008).

It also places digital literacy in the context of lifelong learning, emphasising its continuing relevance beyond formal education. This perspective is in line with the rapidly changing aspect of digital technologies and the importance for continuous skills development throughout life and careers (Eshet, 2004). The image provides a conceptual map that illustrates the multifaceted aspects of digital literacy and its interconnections with various educational and technological aspects.

<Fig.12: The multidimensional approach to digital literacy in contemporary education>

Collaboration:

The analysis emphasised the relevance of multiple perspectives on collaboration, particularly in the context of digital storytelling and future employability. Researchers indicated that collaborative skills are increasingly valued in the workplace and are necessary for career preparation (Binkley et al., 2012). This is in line with the growing recognition of collaboration as a key skill for the 21st century (Dede, 2010).

However, the study also revealed challenges in implementing effective collaboration, particularly in digital environments. The ambiguity of active collaboration in digital storytelling emerged as a primary concern, suggesting the potential benefit of clearer guidelines and expectations in collaborative digital projects (Dillenbourg, 1999). In addition, researchers raised concerns about the potential for bullying in collaborative contexts, emphasising the role of creating safe and inclusive digital spaces for learners (Kowalski et al., 2014).

To address these challenges, research has emphasised the role of empathy and perspective taking in facilitating effective collaboration. These skills are important for navigating diverse perspectives and creating a positive collaborative environment (Niemi et al., 2018). Research has also cautioned against hyper-individualism in collaboration, placing emphasis on the balance between individual contributions and group cohesion (Bruffee, 1999).

The pros and cons of diverse perspectives in collaboration were acknowledged, reflecting the complex landscape of collaborative work. While diversity can enhance creativity and problem solving, it can also lead to conflict if not managed effectively (Jehn et al., 1999). This supports the value of developing students' skills in negotiating different viewpoints and finding shared interests.

<Fig.13: The Complexities of collaboration in digital storytelling and 21st century education>

3.1.3 Researchers' main concerns and issues

The coding analysis of the researchers' responses revealed several key concerns and issues related to the competencies required for KS3 students in an Educational Digital Storytelling (EDS) environment. These concerns provide valuable insights into the potential challenges and considerations for implementing EDS in the classroom.

One of the key issues raised was the potential for collaboration to lead to bullying and disclosure of abuse (P13W). This concern emphasises the requirement for careful monitoring and mediation of collaborative activities in EDS environments to secure a safe and inclusive learning experience for all students (Niemi and Multisilta, 2016). Researchers have also noted that diverse perspectives in collaboration can be both productive and potentially disruptive (P13W), emphasising the importance of facilitating respectful and supportive collaborative environments (Basilotta Gómez-Pablos et al., 2017).

<Fig.14: P13W's responses in 1st Delphi survey using MAXQDA's summary grid>

In terms of digital literacy, while some researchers suggested that KS3 students probably have the required foundation for EDS (P3C), others cautioned against assuming that all young learners are confident with digital tools (P5G). This variation emphasises the importance of assessing and considering individual differences in students' digital literacy skills (Sefton-Green et al., 2016).

Critical thinking was identified as a key skill, with researchers emphasising the requirement for an evolving framework that facilitates adaptability (P14H). However, concerns were raised about the prioritisation of STEM subjects over the arts and humanities, which could inhibit the development of critical thinking and hinder informed citizenship (P1S). This issue emphasises the importance of a balanced curriculum that supports critical thinking skills across a range of subjects (Wegerif et al., 2015).

Researchers also emphasised the value of reflective practices, but cautioned against excessive introspection (P14H). This suggests the case for structured and purposeful reflective activities that promote self-awareness and growth without overwhelming students (Coulson and Harvey, 2013).

<Fig.15: P14H's responses in 1st Delphi survey using MAXQDA's summary grid>

Ultimately, the role of creativity in EDS was discussed, with researchers suggesting that while creativity is important, it does not guarantee alignment with other competencies (P13W). Encouraging risk-taking and overcoming fear of failure were identified as key elements in supporting creative expression, particularly in KS3 children (P1S). This reinforces the requirement for a supportive and challenging environment that values creativity and encourages students to take risks in their learning (Cremin et al., 2018).

<Fig.16: P3C's responses in 1st Delphi survey using MAXQDA's summary grid>

3.1.4 Synthesis of participants' perspectives

The participants' insights provide a comprehensive and sophisticated understanding of the competencies required for KS3 students in an Educational Digital Storytelling (EDS) environment. While each participant provided unique insights, several common themes emerged across their perspectives.

One of the main themes was the interconnectedness of the competencies (P14H, P1S). Participants emphasised that competencies should be considered as an integrated group of skills rather than a hierarchical structure (Katerina Ananiadou and Claro, 2009). This perspective is consistent with the idea that EDS requires a comprehensive approach to skills development, as the competencies interact to support effective learning and storytelling (Niemi et al., 2018).

Creativity emerged as a fundamental skill that facilitates the effective use of other competencies (P14H, P7Q). Participants emphasised the importance of providing a supportive environment for the expression of creativity (P1S), as it can be suppressed by social pressures, particularly among KS3 students (Cremin et al., 2018). However, some participants mentioned the potential conflict between encouraging creative thinking and fulfilling specific competency elements (P13W), emphasising the fact that a balanced approach is required to support creativity in EDS (Ohler, 2013).

Digital literacy was recognised as a critical competency for navigating and expressing oneself in the contemporary environment (P1S). While some participants assumed that KS3 students already had basic digital literacy skills (P3C), others cautioned against overestimating young learners' digital competence (P5G). This difference illustrates the importance of assessing and addressing individual differences in students' digital literacy (Sefton-Green et al., 2016).

Storytelling skills were considered fundamental to the success of EDS (P5G, P9S), with participants emphasising the importance of narrative coherence, character consistency and logical progression (P13W). The role of critical thinking in planning and organising stories was also mentioned (P5G), suggesting that analytical thinking supports narrative integrity (Lipman, 2003).

Collaboration was regarded as a valuable skill that enhances professional careers and personal fulfilment by bridging different perspectives (P1S). However, some participants questioned the assumption that digital storytelling is inherently collaborative (P5G) and raised concerns about the potential for bullying in collaborative environments (P13W). These concerns emphasise the importance of careful monitoring and moderation of collaborative activities in EDS (Basilotta Gómez-Pablos et al., 2017).

Reflective practice was recognised as important for developing self-awareness and supporting personal growth (P14H, P1S). However, participants advised against excessive engagement in reflection, which can lead to unproductive self-absorption (P14H). This suggests the importance of structured and purposeful reflection activities that promote self-awareness without overwhelming students (Coulson and Harvey, 2013).

In conclusion, the synthesis of participants' perspectives reveals the complex and interrelated nature of the competencies required for EDS. The findings reinforce the necessity for a comprehensive, balanced and individualised approach to competence development in EDS, taking into account the unique challenges and opportunities presented by the medium of digital storytelling.

3.1.5 Implications and insights from the initial survey results

3.1.5.1 Core competencies in EDS for language development

The initial survey results indicated a number of key competences that are considered to be fundamental in the Educational Digital Storytelling (EDS) environment for the development of KS3 students' language skills. These competencies, identified as important for language learning in a digital context, are consistent with the findings of Smeda et al. (2014) and Robin (2016), who emphasise the use of multimedia tools to create stories that enhance the learning experience. This approach is in line with constructivist learning theories that focus on authentic contexts and the social dimensions of learning (Vygotsky and Cole, 1978, Kim, 2014), which are important for the development of language skills in the EDS environment.

3.1.5.2 Digital literacy and storytelling in EDS

The competencies identified, including digital literacy, storytelling skills, critical thinking, collaboration, creativity and reflective practice, reflect the multifaceted approach to language learning discussed by Niemi and Multisilta (2016) and Ohler (2013). Niemi and Multisilta (2016) emphasise the importance of developing digital literacy in learners, which includes competencies such as creative thinking, critical thinking, learning to learn, communication, collaboration and social responsibility. They emphasise that digital literacy extends beyond just computer use and includes a range of skills necessary for effective online searching, content creation, problem solving, communication, collaboration and safe online behaviour. This is consistent with the concept of supporting a range of skills beyond traditional literacy in an EDS language learning environment. In addition, Ohler (2013) provides insights into how storytelling activities can support literacy and digital literacy in language learning, discussing how technology in storytelling can make content more understandable and engaging for learners, while emphasising the importance of digital literacy in the digital age.

3.1.5.3 Emphasising a balanced approach in the EDS

Feedback from researchers emphasised the need for a balanced approach to the development of language skills within the EDS framework. This perspective is consistent with the findings of Yang and Wu (2012) and Kimbell-Lopez et al. (2016), who explore how exposure to and engagement with ICT multimedia can influence learners' fluency in language use and expression. These studies support the view of integrating different skills for comprehensive language development in digital learning environments.

3.1.5.4 The importance of digital literacy and storytelling skills in EDS

Digital literacy and storytelling skills were frequently emphasised as basic elements, reflecting the views of Robin (2008) and Alexander (2017). Robin (2008) focuses on the use of digital technology in educational programmes, and discusses an innovative approach to digitally supported contextualised storytelling. The study reinforces the importance of digital literacy in education and provides insights into effective activities using ICT tools. This is consistent with the current study's emphasis on the role of digital literacy and storytelling in educational contexts.

3.1.5.5 The role of reflective practice in learning

The focus on reflective practice in consolidating learning and facilitating metacognition is supported by several research projects which argue that reflection is a key component in enhancing students' understanding and cognitive processes. For instance, Coulson and Harvey (2013) emphasise that teaching metacognition and self-regulation through structured reflection helps students to become better learners. This process involves focusing on the act of learning itself, and managing one's emotions and behaviours to maintain focus and attention. Such practices can increase students' motivation and resilience, leading to more effective learning strategies. In addition, Michalsky and Kramarski (2015) support the integration of reflective practices in learning, suggesting that reflection contributes to the development of metacognitive and social-emotional skills, such as self-awareness and self-regulation. Activities such as blogging, digital storytelling and mind-mapping are identified as effective tools for supporting reflection, enabling students to reflect on their learning, identify new aims and develop strategies for improvement, which are fundamental to lifelong learning.

3.1.5.6 Integrating skills for enhanced learning

The researchers in this study suggested that these skills should not be considered in isolation, but as interrelated elements that combine to enhance students' language skills and overall learning experience. This comprehensive approach to skills development is further supported by Falloon’s (2020) study, which demonstrates the importance of combining different digital literacies to enhance teacher effectiveness in higher education environments. In addition, Wang et al. (Wang et al., 2020a) focused on the role of digital literacy during the pandemic, specifically examining self-efficacy and its relationship with student satisfaction, withdrawal intention and grade point average (GPA). This study supports the view that digital literacy plays a critical role in students' academic success and overall satisfaction.

3.1.5.7 Study limitations

It is important to acknowledge the limitations of this study in order to provide a balanced perspective on the findings. The relatively small sample size (n=8) of the initial survey limits the generalisability of the findings (Faber and Fonseca, 2014). The focus on UK-based researchers may limit the applicability of the findings to other educational contexts (Bray et al., 2014). In addition, the potential for self-selection bias among participants should be considered, as those with a particular interest in EDS may have been more likely to respond to the survey (Bethlehem, 2010). These limitations do not invalidate the findings of the study, but suggest the potential need for further research with larger, more diverse samples to confirm and extend these initial findings.

3.2 Schoolteacher feedback on the pilot prototype

3.2.1 Methodological adaptations in data collection

Initial data collection challenges:

In the early stages of this research project, which aimed to collect detailed feedback from secondary school teachers in England, the primary method of data collection was an online survey distributed via official school email addresses. However, this approach resulted in a lower than expected response rate, requiring a re-evaluation and modification of the data collection strategy. This challenge is consistent with the findings of Dillman et al. (2014) who indicated that email surveys in educational contexts frequently result in low response rates due to the high volume of emails that educators receive on a daily basis.

Adapting the data collection strategy:

To address this issue, a more proactive and accessible approach was taken by designing and distributing inviting tri-folded flyers. These flyers provided concise information about the research project and included a QR code that linked directly to the survey, making it more convenient for potential participants to access and complete the survey. The use of visual tools such as tri-fold flyers has been proven to increase respondent participation in educational research (McCrudden and Schraw, 2007). This strategy was implemented to improve accessibility and encourage participation, as it enabled respondents to interact with the survey immediately and on the move, as opposed to the more formal and easily overlooked email invitations.

Addressing privacy concerns:

During the process of distributing tri-fold flyers, some educators raised concerns about privacy and reluctance to share identifiable information. To alleviate these concerns and maintain ethical compliance, the survey was modified to remove the requirement for participants to provide their name and email address. Instead, non-identifiable demographic information was collected, such as geographical area, employment and approximate age. This change is in line with the recommendations of Singer (2003) who emphasises that providing anonymity to participants can significantly increase response rates, particularly in sensitive areas of research. This adaptation was critical to increasing participation while maintaining ethical standards and respecting participants' privacy.

Methodological flexibility in educational research:

The methodological adaptation described above emphasises the importance of flexibility and responsiveness in research, particularly when conducting research with human participants. As Maxwell (2012) argues, adaptability is a key component of qualitative research, particularly in the rapidly evolving landscape of educational contexts. It is important to be aware of potential biases that may arise from such adaptations, such as the potential impact of flyer distribution on participant demographics. These considerations were taken into account during the analysis phase of the research.

Implications of a modified data collection approach:

Although the feedback obtained through this modified approach lacks specific personal identifiers, it still provides valuable insights into the perspectives and experiences of secondary school teachers in England regarding the feasibility of implementing the Interactive Storybook in a school environment. However, it is important to recognise the potential limitations to generalisability due to the modifications made to the data collection methods. Patton (2014) suggests that even data without personal identifiers can provide meaningful insights into educational trends and teacher perspectives. The insights from this study will be carefully integrated and contextualised within the broader research framework, contributing to the overall findings and conclusions of the project.

Acknowledging potential sampling bias:

In addition to the challenges and adaptations outlined above, it is worth noting that the distribution of flyers may have introduced a potential sampling bias. As the flyers were distributed in specific geographical locations, such as the South West of England, the sample of participants may not be fully representative of the wider population of secondary school teachers in England. This limitation should be acknowledged and taken into account when interpreting the results and drawing conclusions from the data (Etikan et al., 2016).

Balancing limitations and contributions:

Despite these limitations, the adapted data collection approach demonstrated the researcher's commitment to ethical research practice and ability to respond to challenges in the research process. The findings from this study, while not comprehensive, contribute to a further understanding of teachers' perspectives on the integration of interactive educational tools in the classroom. Future research could build on these findings by using more comprehensive sampling methods and exploring the long-term implications of implementing such tools in educational contexts.

<Fig.17: Tri-fold flyer for school teachers' feedback on interactive storybook>

3.2.2 Thematic analysis of educator feedback

The coding analysis of the educators' feedback provided valuable insights into their perceptions and experiences with the Interactive Storybook. The main codes identified various aspects of the tool's usability, engagement, curriculum integration and feasibility in educational environments.

3.2.2.1 Positive reactions and impressions

Overall, educators expressed positive reactions to the Interactive Storybook, with feedback focusing on three main areas:

Innovation and design: Teachers were impressed with the innovative approach of the interactive story (e03), indicating an appreciation for new educational tools. This is consistent with research suggesting that cutting edge digital resources can enhance student engagement and learning outcomes (Dwyer, 2016).

Navigation and usability: Positive feedback was received on aspects of design and navigation. In particular, educators appreciated 'the clearly defined links to further areas of study' and 'the use of colour to block out sections of the page to help segment the information presented - making it less imposing and easier to navigate' (0f6). This feedback supports the importance of user-friendly interfaces in educational technology (Faghih et al., 2014).

Content and resources: Educators found value in the content, with one remarking, "I enjoyed the topic" (b32). They also appreciated the 'usefulness of external resources to support vocabulary', with one teacher stating, 'The links to external resources to support vocabulary understanding is also very useful' (0f6). This positive response to supplementary materials is consistent with research on the benefits of multimodal learning resources (Mayer, 2002).

These positive responses suggest that the Interactive Storybook effectively incorporates elements that educators find valuable for potential classroom implementation. However, further research would be needed to assess its long-term impact on student learning outcomes.

<Fig.18: Positive reactions and impressions from educator feedback>

3.2.2.2 Areas for improvement

While educators generally responded positively to the Interactive Storybook, they also identified several areas for improvement:

Accuracy and appropriateness of AI content: Some educators expressed concerns about the accuracy and appropriateness of the AI-generated content. One teacher noted, "Some of the websites that use AI did not seem to be completely accurate or appropriate for the material" (B32). This emphasises the importance of careful curation and verification of AI-generated educational content, a concern reflected in recent literature on AI in education (Zawacki-Richter et al., 2019).

Navigation and content structure: Feedback indicated a concern for improved navigation and content organisation. One educator suggested that "maybe it needs to be broken down into more user-friendly sections ... so you're not wandering and wandering and wandering" (B32). This is consistent with research emphasising the role of intuitive navigation in digital learning environments (Lim et al., 2021).

Improving the user experience: Overall feedback points to a requirement for improved user experience, particularly in terms of content segmentation and ease of navigation. This reflects the growing emphasis on user-centred design in educational technology (Karampelas, 2020).

These areas for improvement provide valuable insights for refining the Interactive Storybook. Addressing these issues could enhance its effectiveness as an educational tool and increase its adoption by educators.

<Fig.19: Areas for improvement identified in educator feedback>

3.2.2.3 Potential distractions and challenges

While the Interactive Storybook provides interesting learning opportunities, educators expressed concerns about potential distractions that could affect its effectiveness:

Student focus: A key concern raised was the potential for students to be distracted from the main educational objectives. As one educator noted, 'it might be difficult with students, so they might get distracted from the main focus' (0f6). This is consistent with research on the double-edged nature of technology in education, where engaging features can sometimes distract from learning objectives (Bulman and Fairlie, 2016).

Cognitive load: the interactive features of the tool, while engaging, may raise challenges in terms of managing students' cognitive load. This concern reflects ongoing discussions in educational technology about balancing interactivity with focused learning (Mayer and Moreno, 2003).

Classroom management: The potential for distraction raises questions about effective classroom management strategies when implementing such interactive tools. This reflects findings on the requirement for customised pedagogical approaches when integrating digital technologies in the classroom (Tondeur et al., 2017).

These concerns reinforce the importance of designing educational technologies that balance engagement with purposeful learning. Future iterations of the Interactive Storybook could benefit from features that help direct students' attention and support educators in managing potential distractions.

<Fig.20: Potential distractions and challenges identified by educators>

3.2.2.4 User experience and interface design

The feedback from educators revealed several positive aspects of the user experience and interface design of the Interactive Storybook:

Ease of navigation: Educators reported that the tool was "technically easy to navigate for the intended age group, as links are well defined and information is broken down into bite-sized chunks" (0f6). This is consistent with best practice in educational technology design, which emphasises the importance of age-appropriate navigation (Falloon, 2013).

Clarity of interface: The clarity of the user interface was particularly noted, with one educator stating that "the icons are clear and it's obvious what you're clicking on" (B32). This reflects the importance of intuitive design in educational software, which can have a significant impact on learning outcomes (Nokelainen, 2006).

Accessibility of content: The immediate accessibility of content was emphasised as a positive feature. One educator commented: "The instructions are very easy to follow and the content appears immediately. Some of my students have short attention spans and they like to see the content immediately - as opposed to waiting for the content to load' (B32). This aspect responds to the requirement for engaging and quickly accessible content, particularly for students with attention issues (Zheng and Warschauer, 2015, Mayer, 2014).

These findings suggest that the design of the Interactive Storybook successfully incorporates key principles of user-centred design for educational technology. The tool's ability to present information in manageable units, provide clear navigation, and provide immediate access to content aligns well with the desires of both educators and students.

<Fig.21: Educator feedback on user experience and interface>

3.2.2.5 Engagement and content appropriateness

The feedback from educators revealed several positive aspects regarding the level of engagement and content appropriateness of the Interactive Storybook:

Age-appropriate content: Educators remarked on the appropriateness of the vocabulary, images and quizzes for the target age group. One teacher commented: "With the use of the vocabulary, the pictures and the quiz, it is quite good for this age group I would say" (E03). This is consistent with research emphasising the importance of age-appropriate content in educational technology (Hirsh-Pasek et al., 2015).

Engagement through multimedia: The use of different multimedia elements was emphasised as a strength. One educator observed, 'There are some things that might help to keep their attention (such as the embedded video clips)' (0f6). This finding supports the multimedia principle in instructional design, which suggests that people learn more from words and pictures than from words alone (Mayer, 2014).

Content length and student interest: The brevity and structure of the content was considered beneficial for maintaining student engagement. As one educator stated, "I found that the content would have kept my students engaged and interested because it was all very short. They would not have lost interest" (B32). This is consistent with research on optimal content segmentation for digital learning materials (Chen and Wu, 2015).

These findings suggest that the Interactive Storybook effectively incorporates key principles of engagement and age-appropriate content design. The tool's use of multimedia elements, appropriate vocabulary and concise content structure appear to be suitable for maintaining student interest and facilitating learning.

<Fig.22: Educator feedback on engagement and content appropriateness>

3.2.2.6 Navigation and linking

Intuitive navigation and accurate linking:

Educators reported that the content was intuitive to navigate, with links leading to the expected content based on their labels and headings. One educator noted: "All the links led to the exact content I would have expected based on the links and headings" (B32). This alignment between educators' expectations and actual content is important for efficient use of educational resources and can lead to increased cognitive absorption when using technology (Agarwal and Karahanna, 2000).

Suggestion for enhanced content structure:

Some educators suggested that navigation could be improved if the overall 'storybook' structure was extended over more pages. One schoolteacher commented: "If the overall 'storybook' was on more pages, I feel it would be a bit easier to navigate" (B32). This feedback suggests a potential preference for a more detailed content structure that could improve the findability and orientation of information within the site, which would be particularly beneficial for educators searching for specific learning materials (Lazar et al., 2017).

Scope for optimising navigation:

While the current navigation system appears to satisfy basic usability standards for educational purposes, there is potential for optimisation. Implementing a comprehensive site map, improving thread navigation, or introducing a more sophisticated search feature designed for educational content could address educators' suggestions and further improve their overall navigation experience (Nielsen, 1994).

The need for diverse usability testing:

It is important to note that navigation preferences may vary between different groups of educators. Therefore, conducting usability testing with a diverse group of teachers from different grade levels and subject areas and using techniques card sorting (users group and categorise content items) or tree testing (users try to find items within a proposed site structure) could provide more detailed insights to adapt the navigation structure to the specific requirements of educators (Krug, 2000). In addition, considering cognitive load theory in the design of educational websites can help optimise the learning experience for both educators and learners (Plass et al., 2010).

<Fig.23: Educators' feedback on navigating and linking to educational websites>

3.2.2.7 Content relevance and enrichment

Variety of content for learner engagement:

Educators appreciated the variety of content in the storybook. One educator commented, "I liked the pictures and the content was varied. It would appeal to many different learning styles" (B32). This is consistent with the principle of Universal Design for Learning (UDL), which emphasises the importance of providing multiple means of engagement to accommodate diverse learner requirements (CAST, 2018).