Selection and categorisation of Delphi survey participants to explore key language competences in KS3 students: Method and results

- BJ

- 2024년 5월 17일

- 69분 분량

A systematic approach to selecting and categorising Delphi survey participants for exploring the feasibility of a pilot prototype in the enhancement of language skills in KS3 students

This study focuses on the process of selecting and categorising participants for a Delphi survey aimed at defining key language competences in Key Stage 3 (KS3) students for the development of a pilot prototype. The Delphi technique is a method for achieving expert consensus and the selection of participants is a key element in determining the quality of research findings (Hsu and Sandford, 2007).

In this study, three strategies were used to select experts from the areas of language learning, digital technology and creative writing: university department based, personal network based and keyword based. Each strategy is based on theoretical foundations such as stakeholder theory, knowledge creation theory, and grounded theory, which secures a diverse panel of experts with various perspectives (Freeman, 2010; Nonaka and Von Krogh, 2009; Charmaz, 2014).

The profiles and research backgrounds of the selected experts were systematically analysed using MAXQDA software. Through coding, the main areas of expertise of each expert and their potential to contribute to the development of KS3 students' language skills were identified. The results of the analysis were presented using various visualisation tools.

This systematic process of selecting and categorising participants is expected to increase the reliability and validity of the Delphi survey. In addition, this study serves as an archetype of the importance of participant selection and methodological considerations in educational research using the Delphi technique.

The panel of experts selected as a result of this study will participate in the subsequent Delphi survey to reach a consensus on the key language skills of KS3 students. It is expected that this will have practical implications for language learning in the digital age and will contribute to broadening theoretical discussions on language learning.

1. Introduction

This research aims to explore an approach to the selection and categorisation of Delphi survey participants to identify key language competences for Key Stage 3 (KS3) students. The Delphi method, an iterative process involving the collection and synthesis of anonymous expert agreement through questionnaires and feedback, has been used in a variety of research areas (Hsu and Sandford, 2007). The debate about the selection and categorisation of participants in such studies is still evolving and open to further refinement (Schmidt, 1997). Defining key language skills through a well-conducted Delphi survey can provide invaluable insights that can be instrumental in enhancing KS3 students' language skills and informing pedagogical strategies, curriculum development and student assessment protocols (Brown, 2006).

1.1 Literature review

1.1.1 Traditional selection of participants in Delphi surveys

The selection of participants in Delphi surveys has traditionally been based on principles such as securing a diverse and representative panel of experts, their availability and willingness to participate, and the relevance of their expertise to the aims of the study (Day and Bobeva, 2005). More recently, there has been a shift towards more structured selection processes that consider factors such as professional background, years of experience and recognition in the field (Adler and Ziglio, 1996). These factors are typically assessed through peer nominations or objective measures of expertise such as publication record and years of experience (Boulkedid et al., 2011).

1.1.2 Evolution of the selection criteria

Recent research such as Keeney et al (2011) has emphasised the importance of using more adaptive selection approaches, especially in studies that focus on specific competencies such as English language skills for KS3 students. Traditional selection methods may lack specificity and have limitations when applied to targeted subject areas (Jones and Hunter, 1995). For instance, in defining the key elements necessary to enhance language skills within the subject of English Literature for KS3 students, it was not sufficient to focus only on the traditional elements required and assessed by conventional experts.

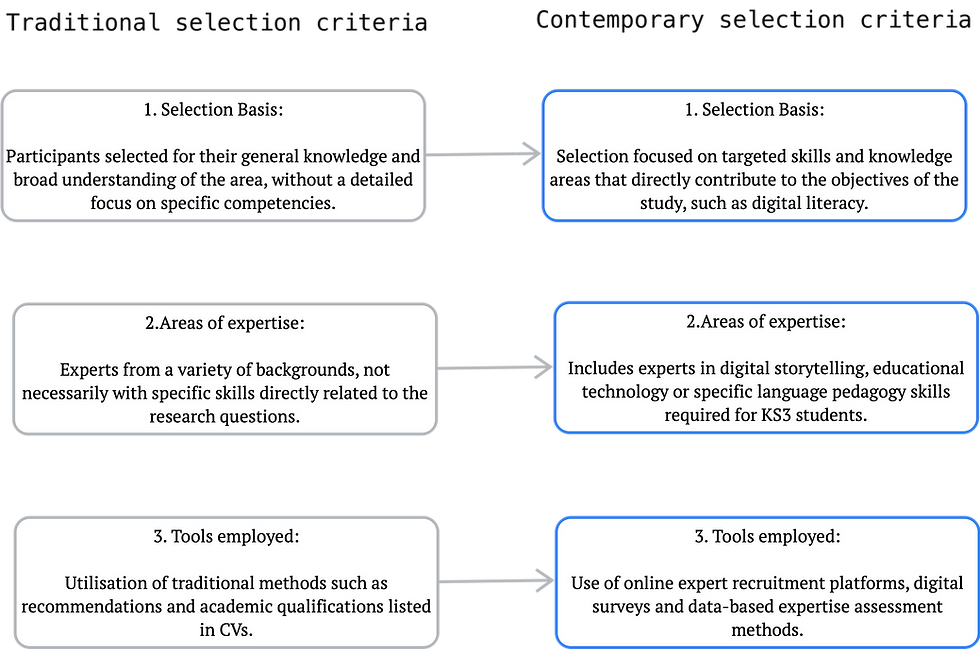

1.1.3 Comparative analysis of traditional and contemporary approaches to participant selection

The diagram in Figure 1 provides a concise visual comparison between the traditional and contemporary approaches to participant selection in Delphi surveys. It emphasises the key changes in the selection base, areas of expertise and tools used in each approach (Skulmoski et al., 2007, Okoli and Pawlowski, 2004).

1.1.3.1 Shifting the focus of selection

The traditional approach considers participants' general knowledge and broad understanding of the research area, rather than a detailed focus on specific competencies. In contrast, the contemporary approach emphasises targeted selection based on skills and knowledge areas that directly contribute to the objectives of the study, such as digital literacy (Hasson et al., 2000, Hsu and Sandford, 2007).

1.1.3.2 Developing areas of expertise

Whereas the traditional approach involves experts from a variety of backgrounds, not necessarily with skills related to the research questions, the contemporary approach involves experts with specialised skills relevant to the study. For instance, in the context of language education, this might include expertise in digital storytelling, educational technology, or specific language pedagogy skills required for KS3 students (Robin, 2008, Smeda et al., 2014, Ohler, 2013).

1.1.3.3 Advances in selection tools

The traditional approach based on manual tools such as peer nominations and CV assessments. However, the contemporary approach makes use of digital tools and sophisticated data analysis techniques (Turoff and Linstone, 2002). This shift facilitates the use of online platforms for expert recruitment, digital surveys, and data-based methods to assess expertise, increasing the effectiveness of the selection process (Niederhauser and Lindstrom, 2018, Donohoe and Needham, 2009).

The comparative analysis presented in the figure reinforces the importance of customising participant selection approaches to the specific requirements and objectives of the study. By focusing on targeted skills, incorporating specialised expertise and utilising advanced tools, the current approach aims to assemble an expert panel that is suited to contribute insights that respond to the research questions (Boulkedid et al., 2011; Powell, 2003).

1.1.4 Integrating digital literacy and narrative competence into language assessment

In the contemporary educational landscape, digital literacy and narrative skills have emerged as integral components of language proficiency (Pérez-Escoda and Rodríguez-Conde, 2015). This shift requires a comprehensive assessment of these skills when assessing language competences, especially in the context of educational digital storytelling (Robin, 2008, Smeda et al., 2014). Therefore, it can be important to consider not only traditional language skills, but also learners' ability to use digital tools and engage in narrative construction when assessing their overall language skills.

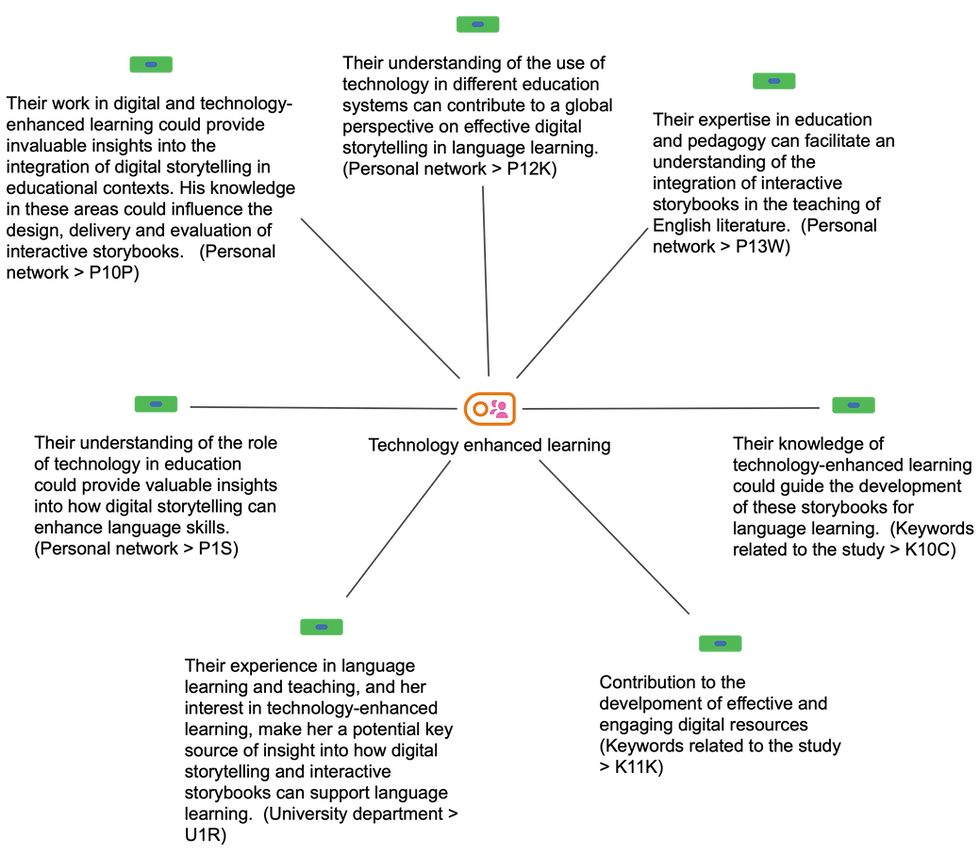

1.1.5 Hierarchical model of language proficiency: From generic to digital narrative skills

The diagram in Figure 2 presents a hierarchical model of language skills, emphasising the progression from general language skills to more specialised digital storytelling skills. At the basic level, learners develop core language skills such as reading, writing, listening and speaking (Grabe & Stoller, 2013). Building on these core skills, learners develop more sophisticated skills such as critical thinking, creativity, and collaboration, which are important for communication in a range of contexts (Partnership for 21st Century Skills, 2019).

As learners progress, they develop digital literacy skills that enable them to navigate and use digital tools and platforms for communication and expression (Eshet-Alkalai, 2004). At the higher levels of the hierarchy, learners develop digital narrative skills, which include the ability to construct and communicate engaging stories using digital media (Alexander, 2011). These skills involve a combination of traditional storytelling techniques and the effective use of digital tools to create immersive narratives.

The hierarchical model presented in the diagram emphasises the importance of integrating digital literacy and narrative competence into the assessment of language skills in the contemporary educational context. By considering these higher-order skills alongside core language skills, educators and researchers can gain a more comprehensive understanding of learners' overall language competence and their ability to communicate effectively in the digital age.

1.1.6 Implications for Delphi Methodology in Language Education

As the Delphi method continues to be a popular choice for conducting studies in various disciplines, including language education (Okoli and Pawlowski, 2004), there is a need to consider the selection and categorisation of participants to reflect the aims of the study. The findings of the study contribute to this ongoing discourse by offering an alternative approach to the selection and categorisation of participants in Delphi surveys.

1.2 Identified gap in existing literature

1.2.1 Overview of current applications and gaps

Despite the extensive use of Delphi surveys in educational research (Okoli and Pawlowski, 2004), a gap in the literature relates to the selection and categorisation of participants, particularly when defining key language skills (Hsu and Sandford, 2007). Many studies make insufficient distinction between areas of language competence or grade levels in their expert selection process, potentially resulting in a less than ideal mix of expertise and limiting the effectiveness of the Delphi process.

1.2.2 Historical and methodological background

The foundational work of Delbecq et al. (1975) establishes the broad applications of the Delphi method, while Yousuf (2007) discusses the critical methodological considerations, emphasising the importance of accurate expert selection.

1.2.3 Specific applications in education and health sciences

More specific to educational contexts, Uztosun (2018) demonstrates the importance of targeted expertise in defining competences for English language teaching, de Villiers et al. (2005) emphasise the role of expert consensus in health sciences education, and Mengual-Andrés et al. (2016) validate the use of Delphi in assessing digital competences in higher education.

1.2.4 Proposed refined selection approach

To address this issue, this study proposes a refined selection approach that categorises experts into three distinct groups: those affiliated with university departments related to the research topic (Akins et al., 2005), those within the researcher's personal network (Hsu and Sandford, 2007), and those identified through relevant research keywords (Landeta, 2006). This specific categorisation enhances the validity and reliability of the study (Keeney et al., 2001) and provides a replicable model for future Delphi studies, particularly in the area of language competency (Dalkey et al., 1969).

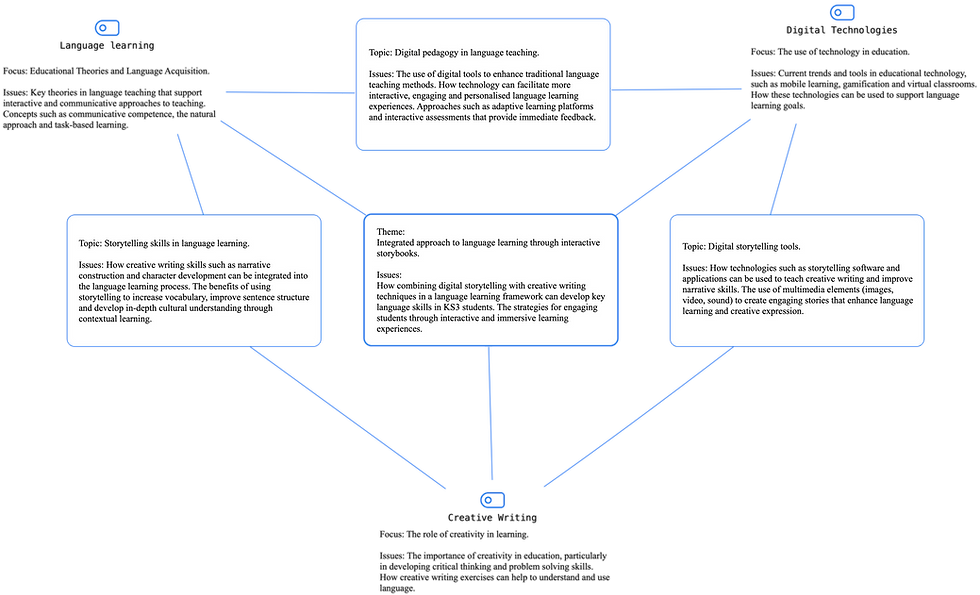

1.2.5 Concept map of research gaps and proposed approaches

The concept map presented in Figure 3 provides an overview of the identified gaps in existing selection methods for Delphi participants and the proposed approaches to alleviate these limitations. This visual representation summarises the key points discussed in the previous sections and provides a logical framework for understanding the rationale behind the refined selection approach (Novak & Cañas, 2008).

1.2.5.1 Identified gaps in existing selection methods

The concept map identifies three main gaps in traditional selection methods for Delphi survey participants. First, these methods may lack specificity, when applied to targeted subject areas such as English language skills for KS3 students (Jones and Hunter, 1995). Secondly, traditional methods have led to limited integration of digital skills, which are increasingly important in contemporary educational contexts (Pérez-Escoda and Rodríguez-Conde, 2015). Finally, reliance on peer nomination and general expertise may not always yield the most appropriate participants for a given study (Hsu and Sandford, 2007).

1.2.5.2 Proposed new approaches to selection

To respond to these issues, the concept map presents three key approaches for refining the selection process. For the specific gap, the proposed approach includes a criteria-based selection focusing on digital literacy and storytelling skills, which are essential for assessing language skills in the context of educational digital storytelling (Robin, 2008). To reduce the digital literacy gap, the approach introduces criteria that include digital storytelling skills, recognising the growing importance of these skills in language education (Smeda et al., 2014). Finally, to alleviate the reliance on traditional methods, the proposed approach recommends the use of data analytics and digital platforms to identify and select experts (Turoff and Linstone, 2002).

1.2.5.3 Anticipated impact of new approaches

The concept map also outlines the expected impact of implementing these emerging approaches. By adopting targeted and criteria-based selection process, the research aims to improve the focus on specific educational objectives and enhance the ability to evaluate contemporary educational tools and methods (Niederhauser and Lindstrom, 2018). In addition, the integration of data-based methods and digital platforms is expected to increase the reliability and validity of the participant selection process (Skulmoski et al., 2007).

The visual representation of research gaps, proposed approaches and anticipated impacts in the concept map provides a comprehensive and understandable summary of the key issues and approaches discussed in the literature review.

1.3 Research questions

1.3.1 Defining effective participant selection and categorisation

Given the identified gap in the existing literature, this study aims to answer two interrelated primary research questions. Firstly, what is an effective way of selecting and categorising Delphi survey participants in order to define the key language competences of KS3 students? This involves not only identifying suitable experts, but also differentiating them according to their specific areas of expertise.

1.3.2 Evaluation of the impact of the new selection procedure

Secondly, what are the results and implications of using this new method for selecting and categorising participants in a Delphi survey? This question aims to assess the effectiveness of the proposed method and its potential impact on the results.

1.3.3 Meaning of research questions in educational Delphi studies

The importance of these questions is in their potential to enhance the reliability and validity of Delphi studies in education, particularly those focused on defining key competences in specific subject areas and grade levels (Turoff and Linstone, 2002). In addition, this study is notable for its specific focus on the process of selecting and categorising participants, which has not been thoroughly investigated in the context of defining language competences in education.

1.3.4 The role of the Delphi approach in responding to research questions

The Delphi method, with its iterative process of expert feedback, is uniquely suited to responding to these issues because of its ability to capture and consolidate diverse expert insights (Dalkey et al., 1969).

1.4 Theoretical framework

1.4.1 Participant Selection Strategy

The decision to divide potential Delphi survey participants into three distinct categories - those from specific university departments, those from a personal network, and those identified by keywords - was made with the aim of securing comprehensive, diverse and valuable perspectives for the study.

1.4.2 Principles of Participant Selection

The selection process for participants in this study follows the principles suggested by McNamara (2009) and Yousuf (2007). They suggest three key considerations when selecting research participants: expertise, experience, and insight into the research topic. These principles were applied in this study by structuring them into three categories.

1.4.2.1 University Department:

-Selection rationale for the University Department category:

Firstly, the category 'university department' was selected because it directly identifies researchers and academics in fields that intersect with the topic of an interactive storybook and language learning. This provides for the inclusion of experts who, through their expertise and active involvement in the field, can provide an in-depth understanding and insight into this particular area of study.

-Methodology of content analysis for participant identification:

In terms of methodology, the approach taken to identify potential participants within the university department was primarily based on a content analysis methodology. Content analysis is a research tool used to determine the presence of particular words, themes or concepts within a given set of qualitative data (Krippendorff, 2018). This method was selected for its flexibility and systematic approach, making it ideal for exploring large amounts of textual data within academic publications (White and Marsh, 2006).

-Approaches and progress in content analysis:

Different approaches to content analysis, such as conventional, directed or summative, provide various ways of extracting meaningful data from texts, each of which is appropriate depending on the specific research objectives (Hsieh and Shannon, 2005). Furthermore, emerging methods in content analysis can facilitate the efficient and transparent processing of textual data, which can assist in the accurate identification of research participants (Stepchenkova et al., 2009).

-Inclusion of bibliometric analysis:

An element of bibliometric analysis (BA) was also used, which involves the statistical analysis of written publications, such as books and articles, to understand the interconnectedness of different researchers and how their research contributes to the overall field of interest (Hood and Wilson, 2001). BA was used to identify potential contributors who were frequently published or cited in areas relevant to the research topic.

1.4.2.2 Personal Network:

1.4.2.2.1 Grounds for including the Personal Network category

Secondly, the 'personal network' category was included because it includes researchers and academics who have demonstrated a direct interest in this project or who have previously provided insight and guidance. These participants are in a position to provide insights due to their direct involvement and familiarity with the specific context and aims of the research.

1.4.2.2.2 Application of grounded theory:

The methodology used to analyse potential participants from the personal network is based on Grounded Theory (GT). Based on the desire to understand and analyse patterns directly from empirical data, GT is suitable for exploratory research in which theoretical constructs are developed inductively (Glaser and Strauss, 2017).

In the context of this study, GT is used to

-Engage in iterative data collection and analysis:

Data from interactions, previous projects and informal discussions with potential participants are analysed. This iterative process helps to identify emerging patterns and themes that are important for understanding the depth of participants' knowledge and their potential impact on the study (Currie, 2009).

-Develop conceptual frameworks:

By analysing the data collected from personal interactions, GT helps to develop a conceptual framework that outlines how participants' insights and experiences relate to the enhancement of language skills in the EDS environment.

1.4.2.2.3 Use of Thematic Analysis:

In conjunction with GT, Thematic Analysis (TA) is used to further categorise and understand the potential contributions of each participant. TA is effective for organising and interpreting large data sets, making it an invaluable tool for managing qualitative data (Braun and Clarke, 2006).

-The application of TA involves the following steps:

Coding for themes: Initial codes are generated from the data, reflecting key concepts and ideas mentioned by participants. These codes are then grouped into broader themes that capture the overarching insights related to the research objectives (Attride-Stirling, 2001).

-Refining themes:

The themes are reviewed and refined to reflect the data accurately and to align with the research questions. This involves an iterative process of comparing themes with the dataset to maintain consistency and coherence. Thomas and Harden (2008) provide insights into how to develop and refine descriptive and analytical themes in thematic synthesis.

-Mapping and interpretation:

The final themes are used to map the relationships and interactions between various concepts. This helps to understand how participants' contributions can be integrated into the broader research framework, with a particular focus on their potential to influence educational achievement in the EDS environment. Majumdar (2019) discusses the flexibility and detailed analytical capacity of thematic analysis in qualitative research.

1.4.2.3 Keywords

-Reasons for including the Keywords category

Finally, the 'keywords' category enables the identification of researchers who may not be directly associated with the researcher's university department or personal network, but who have demonstrated expertise in areas related to this project. By focusing on keywords that are highly relevant to this research, such as 'storytelling', 'digital storytelling', 'education' and 'multimedia', this research aims to include a wide range of scholars involved in these areas, who can bring diverse and potentially innovative perspectives to the study.

-Method of participant identification using keywords

The selected keywords were used as a guide to identify potential participants. Researchers who had undertaken projects or published papers related to these keywords were considered as potential contributors to the study. This approach, commonly referred to as 'keyword-in-context' (KWIC) is a method used in qualitative research to make visible the environments in which keywords are used and provides a sound basis for selecting participants who are likely to contribute valuable insights to the research.

-Practical use and benefits of keyword-in-context (KWIC)

The practical application of KWIC in facilitating information retrieval and increasing the visibility of relevant data is supported in the literature, as noted by Fischer (1966) in her discussion of the development and utility of KWIC indices in various research contexts.

-Integrate multiple categories for a broad mix of participants

By combining these three categories, the selection process is designed to provide a rich mix of viewpoints and expertise, which is important for an exploratory and iterative method such as the Delphi survey.

1.4.4 Theoretical Support for Participant Categorization

The approach of selecting participants from three specific categories can be supported by several theoretical perspectives.

1.4.4.1 Stakeholder Theory:

Firstly, from the perspective of stakeholder theory (Freeman, 2010), it's important to involve different stakeholders who have a direct or indirect interest in the phenomenon under study. The different stakeholder groups represented by the three categories - those by university department, personal network and keywords - can provide different perspectives that can lead to more insight. The inclusion of personal network participants is in line with this theory, as these participants often have a direct interest in the study.

1.4.4.2 Knowledge Creation Theory:

Secondly, from the perspective of knowledge creation theory (Nonaka and Nishiguchi, 2001), knowledge is created through the interaction of tacit and explicit knowledge in different contexts. The university department category captures explicit knowledge from formal academic disciplines, while the personal network category can provide insights based on tacit knowledge from personal experiences and relationships. This interaction between tacit and explicit knowledge, which is important for effective knowledge creation and application in organisations, is discussed in the study of Nonaka and Von Krogh (2009), who explore the details and implications of these processes in organisational contexts.

1.4.4.3 Grounded Theory:

Finally, from a grounded theory perspective (Glaser and Strauss, 2017), the process of constant comparative analysis involves comparing new data with existing data to develop theoretical constructs. The inclusion of keyword-identified participants may facilitate this process of comparison, as these participants may provide new insights that challenge or complement the views of the university department and personal network categories.

By using these theoretical perspectives, the selection process for Delphi survey participants can be regarded as sound and theoretically informed, resulting in the collection of a comprehensive and diverse set of data.

1.4.4.4 Theoretical foundations supporting the participant selection approach

The diagram in Figure 4 concisely illustrates the theoretical foundations supporting the participant selection approach used in this study. Three main theoretical perspectives are emphasised:

Stakeholder theory (Freeman, 2010) emphasises the importance of involving various stakeholders who can influence or benefit from the study, supporting the inclusion of participants from university departments and personal networks.

Knowledge creation theory (Nonaka and Nishiguchi, 2001) supports the selection of participants based on their potential to facilitate the interaction between intuitive and expert knowledge, which is important for the generation of new knowledge (Nonaka and Von Krogh, 2009).

Grounded theory (Glaser and Strauss, 2017) advocates the iterative comparison of emerging and existing data to refine theoretical constructs, consistent with the inclusion of keyword-identified participants who may contribute new insights that may challenge existing paradigms (Charmaz, 2014).

These emerging theoretical frameworks emphasise the importance of stakeholder engagement, knowledge generation and iterative data comparison, increasing the methodological consistency and potential impact of the Delphi study.

1.5 A comprehensive approach to participant selection in a Delphi study on digital storytelling for language learning

1.5.1 Traditional selection: Building a foundation

The diagram provides a visual representation of the structured and adaptive participant selection process used in this study. Selection begins with a traditional approach based on diversity, availability and overall relevance to the study objectives (Skulmoski et al., 2007).

1.5.2 Structured selection: Refining the participant pool

This initial selection is then refined through a structured process that includes criteria such as professional background, experience and recognised expertise, assessed through peer nominations and objective measures (Okoli and Pawlowski, 2004).

1.5.3 Adaptive selection: Focusing on specific competencies

The selection process is further enhanced by adaptive approaches that focus on specific competencies required for KS3 students, such as language skills and pedagogical methods (Hasson et al., 2000). These approaches are iteratively refined based on feedback to keep the criteria relevant and aligned with the research objectives (Keeney et al., 2006). This iterative process keeps the selection criteria responsive to the evolving demands of the study and the targeted student population (Skulmoski et al., 2007).

1.5.4 Iterative feedback and refinement of criteria

As indicated in the diagram, the selection process incorporates an iterative feedback loop to refine the criteria on an iterative basis. If it becomes obvious that more emphasis needs to be placed on particular digital skills or competences, the criteria will be adjusted to reflect this issue. This continuous refinement makes sure that the selected participants have the most relevant and current expertise to contribute to the objectives of the study (Okoli and Pawlowski, 2004).

1.5.5 Expanded digital literacy criteria

The digital literacy criteria are also extended to include storytelling skills, recognising the importance of digital storytelling in the context of this study (Robin, 2008). This extension secures that the selected participants have the necessary expertise to provide valuable insights into the application of digital storytelling in educational contexts (Smeda et al., 2014). The iterative feedback process helps to identify and incorporate these additional criteria, providing a comprehensive and targeted selection approach.

1.5.6 Final selection: The Delphi method

Finally, the ultimate selection is based on the Delphi method, which focuses on improving the validity and reliability of research findings (Turoff and Linstone, 2002). By employing a consistent, adaptive, and iterative selection process, this study aims to assemble a panel of experts who are suitable to contribute to the development of strategies for enhancing language skills through digital storytelling (Niederhauser and Lindstrom, 2018). The Delphi method's emphasis on expert consensus and iterative feedback aligns with the study's participant selection approach, securing a reliable foundation for the research.rom, 2018).

2. Research Methods

The research methods of this study include a mixture of traditional approaches and new procedures explicitly designed for the selection and categorisation of Delphi survey participants in the area of English language competence for KS3 students. The aim is to secure a diverse, representative and highly relevant panel of experts.

2.1 Design of the Delphi survey

2.1.1 Overview of the Delphi survey

In line with the principles of a structured communication technique, the Delphi survey of this study uses multiple rounds of questionnaires and feedback to achieve convergence of opinion (Turoff and Linstone, 2002).

2.1.2 Expert selection criteria

To achieve this, a set of selection criteria for experts was developed in three categories, taking into account each participant's professional background, years of experience and the relevance of their expertise to the key English language competences of KS3 students. The importance of such customised selection criteria is emphasised by Okoli and Pawlowski (2004), who indicate the importance of expert diversity and depth of knowledge for effective Delphi studies. Furthermore, Hsu and Sandford (2007) and Rowe and Wright (2001) emphasise the value of a careful selection process to focus expert knowledge on specific research objectives, thereby enhancing the validity and applicability of findings.

2.1.3 Categorisation of Experts

2.1.3.1 University Department Experts:

The first category includes researchers from university departments such as Education, Media, Interactive Media, Media Production, Media and Communication, Digital Media, Publishing Media, Media and Creative Industries and Multimedia Storytelling. These departments are closely related to the focus of this research, with researchers demonstrating interest and expertise in areas such as interactive storybooks, digital media and their educational applications. The importance of such expertise is supported by studies such as Lacka and Wong (2021), who illustrate the impact of digital technologies in higher education, and Herro et al. (2017), who discuss the benefits of university-school partnerships in promoting digital media learning in the classroom.

2.1.3.2 Personal network experts:

The second category includes researchers from the researcher's personal network who have provided valuable insights throughout the research process. These include researchers from the University of Plymouth who have taught and supervised the researcher's MA Publishing programme, and those from the Plymouth Institute of Education (PIoE) who have provided advice on this research topic. The relevance of using personal networks in research is supported by studies such as that of Tsikerdekis (2016), who provides evidence of how personal communication networks significantly improve collaboration and the quality of findings. In addition, Schultz and Schultz and Schreyogg (2013) provide empirical evidence on the impact of network relationships and resource contributions on research performance, emphasising the importance of personal networks in academic research environments.

2.1.3.3 Keyword-associated experts:

The third category includes experts associated with specific keywords relevant to the study, including storytelling, digital storytelling, education, KS3 students, GCSE exams, curriculum enrichment and multimedia. This approach aims to include a diverse range of expertise directly related to the research topic. The importance of using keywords to guide the selection of experts is supported by Cooper and Ribble (1989) , who found that the expertise of the searcher influenced the results of literature searches in integrative research reviews. Their study emphasises the importance of the researcher's ability to select relevant keywords that are closely related to the aims of the study, enhancing the quality and applicability of the expert panel.

By distinguishing experts according to these categories, the study provided adequate representation of each aspect of English language competences for KS3 students and drew on a wide range of expertise and perspectives, thereby increasing the validity and richness of the findings.

2.1.3.4 Impact of participant categorisation on research results

The categorisation of participants in the Delphi survey, as illustrated in Figure 2.1, was designed to secure a diverse and representative panel of experts. This approach is expected to enhance the validity and comprehensiveness of the research findings by providing a wide range of expertise and perspectives in relation to the language skills of KS3 students (Okoli and Pawlowski, 2004, Hsu and Sandford, 2007).

The inclusion of experts from university departments will contribute insights into the pedagogical applications of digital technologies and interactive storybooks, which can inform the development of strategies to enhance language skills (Lacka and Wong, 2021, Herro et al., 2017). Personal network experts, on the other hand, may contribute to the quality of findings through enhanced collaboration and exchange of shared knowledge (Tsikerdekis, 2016, Schultz and Schreyogg, 2013).

Keyword-associated experts, identified based on their association with specific keywords relevant to the study, make sure that the research includes a wide range of expertise directly related to the research topic. This targeted approach can lead to more applicable findings (Cooper and Ribble, 1989).

By utilising the unique strengths of each participant category, the study aims to generate findings that are not only reliable, but also relevant for improving the English language skills of KS3 students.

2.2 Identification of potential participants

2.2.1 Using purposive sampling for initial participant identification

Potential participants were identified using a combination of purposive and snowball sampling techniques (Goodman, 1961). An initial list of potential participants was generated by contacting the websites of university departments and research institutions. This followed the principles of purposive sampling (Tongco, 2007), a non-probability sampling technique often used in qualitative research. This technique focuses on selecting participants based on their specific characteristics or expertise, thereby enabling them to contribute meaningful data to the research (Palinkas et al., 2015).

2.2.2 Consistency of participant selection across categories

For the category 'Researchers identified by keywords related to the study', a similar approach was used as for the category 'Researchers identified by university department'. This approach involves a detailed analysis of the published works, professional activities and public academic profiles of potential participants to confirm that their expertise is in line with the focus areas of the study, such as digital storytelling, education and multimedia applications. Both approaches emphasise the need for a systematic method of evaluating overall expertise and its applicability to the aims of the study, while also recognising the individual, insights that each expert might bring (Hsu and Sandford, 2007). This methodological similarity is important as it provides a consistent and thorough selection process across different categories, increasing the general validity and reliability of the participant selection process.

2.2.3 Integrating snowball sampling to expand the participant pool

Snowball sampling facilitated the identification of additional participants through the personal networks of these initial contacts. Although personal networks could introduce potential bias, it was felt that their ability to provide an in-depth understanding of participants' interests and abilities would offset this bias and contribute to the research. Maintaining transparency in the selection of participants to mitigate potential bias is critical to maintaining the credibility of the study. Studies such as Marcus et al. (2017) and Petersen and Valdez (2005) emphasise the importance of identifying potential biases in snowball sampling and provide strategies to mitigate these issues, providing a more reliable and credible research outcome.

2.2.4 Evaluating and balancing the selection criteria

Each potential participant was then assessed against the three categories of selection criteria developed for this study. The aim was to achieve a balanced representation of the different areas of expertise required to define key English language competences for KS3 students (Turoff and Linstone, 2002). The dual approach to analysis, in line with the principles of purposive sampling, will identify both the general thematic areas of overlap with the study and the unique contributions that individual researchers might make, thereby enhancing the reliability of the Delphi study (Campbell et al., 2020, Goodarzi et al., 2018).

2.2.5 Participant identification and selection process

The diagram in Figure 2.2 illustrates the systematic process used in this study to identify and select participants for the Delphi survey. The process begins with two initial sampling strategies: purposive sampling, which involves targeting participants based on their relevant expertise and experience, and snowball sampling, which includes expanding the participant pool through recommendations and networks of initially selected individuals (Palinkas et al., 2015).

The evaluation stage involves a thorough assessment of each potential participant's suitability for the study's selection criteria, making sure that there is a balanced representation of expertise across the identified categories (Hasson et al., 2000). This evaluation process, which includes analysis of academic profiles, publication records and professional contributions, enhances the validity and reliability of the participant selection process (Skulmoski et al., 2007).

The result of this process is a selected panel of experts who are expected to contribute a wide range of insights into the implementation of interactive storybooks in English language learning for KS3 students. By integrating diverse expert opinions, the study aims to achieve a comprehensive understanding of the subject area, leading to reliable findings that can inform pedagogical practice and curriculum development (Delbecq et al., 1975).

The selection process will secure that each participant's expertise contributes to the overall research objectives, enhancing the relevance of the research findings for the target population of KS3 students (Powell, 2003). This approach will provide confidence that the results of the Delphi survey will be informed by a diverse and knowledgeable panel, able to respond to the specific challenges and opportunities within innovations in English language learning for KS3 students.

2.3 Analysis and categorisation of potential Delphi survey participants

2.3.1 Systematic Approach to Participant Categorization

The selection and categorisation of potential Delphi survey participants was conducted using a systematic approach guided by three primary categories: researchers identified through keywords related to the study, researchers within personal networks, and researchers found within specific university departments. As outlined by Skulmoski et al. (2007), these categories can provide a wide and diverse range of expertise and perspectives that can enrich the Delphi process, which is essential when investigating the feasibility of using interactive storybooks to develop the English language skills of Key Stage 3 students.

-Specific analysis methods for each category

However, each category had distinctive characteristics that required the use of differentiated methods of analysis, a strategy advocated by Okoli and Pawlowski (2004), in order to effectively assess their relevance and potential contribution to the study.

-Structured selection and design principles

In support of this approach, Okoli and Pawlowski (2004) emphasise the importance of a structured method for selecting appropriate experts for a Delphi study and outline detailed principles for making design decisions during the process to support a valid study.

-Analysing University Department Researchers

A unified analysis was applied to the category of researchers identified by university department. The similarity of their research areas, such as digital storytelling and educational media, facilitated the grouping of individual research areas into larger thematic areas. This integrated approach, as argued by Rowe and Wright (1999), provides an overview of the collective expertise within the category and its applicability to the study.

2.3.2 Individualized Analysis of Personal Network Researchers

Conversely, the category of researchers within personal networks required a more individualised approach due to the diversity of their research areas. As suggested by Landeta (2006), the expertise of each researcher was assessed individually, which made it possible to identify the specific ways in which each researcher's work could enrich the study, given their different areas of interest. This approach is supported by Jorm (2015), who discusses the application of the Delphi method in mental health research, where individualised analysis is important due to the subjective aspects of the area and the diverse expertise of the researchers involved. This method can be used to strengthen the overall quality and depth of the research by making sure that the unique insights of each expert are utilised.

2.3.3 Keyword based analysis for broad expertise

For the category 'Researchers identified by keywords related to the study', a similar approach can be taken as for the category 'Researchers identified by university department'. This approach, as noted by Hsu and Sandford (2007), provides a means of identifying collective expertise and its applicability to the study, while also recognising individual unique insights. Providing support for this methodology, Niederberger and Spranger (2020) discuss how, in the health sciences, the Delphi technique uses a systematic application of keywords to recruit a diverse panel of experts. This approach is useful in selecting experts who have the required knowledge and experience to contribute to the research questions raised, increasing the reliability of the study's findings.

2.3.4 Using purposive sampling across categories

This approach to analysis follows the principles of 'purposive sampling', a non-probability sampling technique frequently used in qualitative research (Tongco, 2007, Palinkas et al., 2015). This technique focuses on selecting participants based on their specific characteristics or expertise, which in turn helps them to contribute meaningful data to the research. The reliability and strategic importance of purposive sampling in research is further emphasised in studies such as those by Tongco (2007), who discusses its effectiveness in selecting informed participants for ethnobotanical research, and Campbell et al. (2020), who present various case studies demonstrating how purposive sampling enhances the validity and applicability of research findings.

2.3.5 Conclusion: Securing comprehensive and insightful analysis

In conclusion, the application of a dual approach, anchored in the principles of 'purposive sampling', not only provides a comprehensive understanding of the expertise landscape, but also advocates the importance of individual narratives (Palinkas et al., 2015, Patton, 1999, Okoli and Pawlowski, 2004). The combined insights of researchers such as Tongco (2007) and Campbell et al. (2020) emphasise the transformative potential of such analysis and reinforce its important role in increasing the depth of a Delphi study. Tongco's discussion of the strategic use of purposive sampling emphasises its effectiveness in selecting informed participants who provide meaningful data relevant to the research objectives, while Campbell et al. present case examples of how purposive sampling contributes to the methodological consistency of the study.

2.4 Rationale for the selection of participants

2.4.1 Multifaceted approach to participant selection

The Delphi survey method requires participants who are not only familiar with the topic, but also experts who can offer informed opinions and insights. This study's approach to selecting participants is aimed at achieving this level of expertise in a number of ways.

-Selection of participants from university departments

Firstly, by drawing participants from a range of university departments directly related to the research focus, the study helps to secure that the participants selected are professionally engaged with the topic.

-Using personal networks

Secondly, the selection of participants from a personal network built up over the course of the researcher's academic career provides access to individuals who have shown a direct interest in the research topic.

-Utilizing Research-Relevant Keywords

Finally, the use of specific research-relevant keywords as selection criteria facilitates the identification of participants who have made significant contributions in these areas.

2.4.2 Combining sampling strategies to improve reliability

By combining these approaches, the selection process should lead to a group of participants with a diverse yet relevant range of expertise, providing the broad and multifaceted perspective necessary for a successful Delphi study. This approach is based on the notion that combining different sampling strategies can increase the reliability and depth of qualitative research (Etikan et al., 2016).

2.5 Potential bias

2.5.1 Recognising researcher bias

In qualitative research, researcher bias and subjectivity are recognised as inherent parts of the research process (Pannucci and Wilkins, 2010). In this context, the potential for bias exists in the form of the researcher's pre-established relationships with some of the potential participants, which could lead to an unintended bias in the interpretation of the data. Several strategies are used to mitigate this. To address these concerns, Noble and Smith (2015) emphasise the importance for qualitative researchers to enhance the validity and reliability of their research through a variety of methodological approaches, reducing bias and increasing the credibility of their research.

2.5.2 Practicing Reflexivity

Firstly, reflexivity, or self-reflection on the research process, will be practised throughout the study (Berger, 2015). The researcher will engage in constant self-reflection, documenting personal reactions, assumptions and potential biases. This reflexivity note will be referred to throughout the data analysis to ensure that interpretations remain grounded in the data. Dodgson (2019) emphasises that any qualitative research is contextual, taking place between people in a particular time and place. By addressing reflexivity, researchers can increase the credibility of their findings and enhance the understanding of their research. Furthermore, Darawsheh (2014) reinforces the importance of reflexivity in promoting the reliability and validity of qualitative research, indicating that reflexivity is an important tool in maintaining the research process's neutrality.

2.5.3 Employing Methodological Triangulation

Secondly, methodological triangulation is used. By using multiple methods of data collection and analysis, the study can cross-verify its findings and increase the validity of the research. Denzin (1978) initially proposed this concept and it has been further developed by researchers such as Hussein (2009), who discusses the benefits of combining qualitative and quantitative methods to increase the accuracy and depth of the study. In addition, Jick (1979) provides practical insights into how triangulation has been used to integrate various methodologies to improve the quality and reliability of research findings.

2.5.4 Securing transparency in research processes

-Commitment to methodological transparency

Finally, transparency is maintained throughout the research process. Clear and detailed accounts are provided of how data is collected, how participants are selected, how decisions are made during analysis, and how conclusions are drawn (Simons, 2009). This allows readers to scrutinise the research process and potentially identify areas where bias may have been introduced.

-Responding to the complexity of transparency

Bridges-Rhoads et al. (2016) emphasise the complexity of transparency, suggesting that it involves not only clear reporting, but also critical examination of methodological choices.

-Enhancing transparency and reproducibility in qualitative research

In addition, Aguinis and Solarino (2019) identify challenges and strategies for enhancing transparency and replicability in qualitative research, particularly in studies with prominent participants. By implementing these strategies, research aims to mitigate potential bias and secure the validity and credibility of its findings. This provides readers with the opportunity to scrutinise the research process and potentially identify areas where bias may have been introduced.

2.6 Analysis of participants' research history

2.6.1 Clarifying the methodological approach

Before considering the analysis of potential participants, it is important to clarify the methodological basis of the approach. The primary aim of this analysis is to understand how each participant's research history and expertise is relevant to exploring the potential of interactive storybooks in education.

2.6.2 Using a mixed methods approach

In order to achieve this, this study will employ a mixed methods approach using a range of qualitative data analysis tools, a strategy recommended to enhance the range and depth of insights (Leech and Onwuegbuzie, 2007). Specifically, a combination of text analysis, coding, comparative analysis and relational analysis will be employed (Fetters and Molina-Azorin, 2017).

2.6.3 Advantages of methodological triangulation

The triangulation of these complementary analytical techniques facilitates a comprehensive understanding of the complex phenomenon being studied (Leech and Onwuegbuzie, 2007). The integration of multiple qualitative methods provides a more comprehensive view than relying on a single approach. As Fetters and Molina-Azorin (2017) advocate, the revitalisation and combination of established methodological practices can lead to new insights in research findings.

2.6.4 Text Analysis

First, through text analysis, this study will examine the summarised research histories of potential participants, focusing on key words and phrases that suggest a connection to the research topic. MAXQDA software will be used to support the qualitative coding and categorisation of the textual data (Kuckartz and Rädiker, 2019). This approach is in line with established practices in qualitative content analysis (Hsieh and Shannon, 2005). Lacity and Janson (1994) provide a comprehensive framework for understanding and applying various methods of text analysis in qualitative research, which supports the systematic approach taken in this study. The findings will help to identify the areas of expertise, research methods and topics of interest relevant to the potential participants (Krippendorff, 2018).

2.6.4.1 Coding

-Thematic analysis using MAXQDA

Secondly, this study will translate the keywords and phrases from the text analysis into codes using MAXQDA software (Kuckartz and Rädiker, 2019). The coding process will follow the principles of thematic analysis, which is a method for identifying, analysing and reporting patterns within qualitative data (Braun and Clarke, 2006). This approach to coding is widely used in qualitative research and provides a structured way of organising and describing data in detail (Nowell et al., 2017).

-Stages of the coding process

The coding process will involve several stages including initial coding, focused coding and theoretical coding (Charmaz, 2014). Initial coding involves breaking down the data into discrete parts and examining them closely for similarities and differences. In the focused coding stage, the most significant or frequent initial codes will be sorted, synthesised and integrated to develop categories or themes. Finally, in theoretical coding, the core categories will be selected and systematically related to other categories, validating these relationships and adding categories that require further refinement and development (Saldaña, 2021).

-Identifying patterns and themes

This iterative process of coding will facilitate the identification of significant patterns and themes in participants' research histories. For example, it may reveal common research methodologies, theoretical frameworks or key findings that extend across the work of multiple participants. Identifying these patterns can provide a more in-depth understanding of the collective expertise and perspectives that participants bring to the study (Williams and Moser, 2019).

2.6.5 Comparative analysis

2.6.5.1 Methods of comparative analysis

Following the coding process, this study will conduct a comparative analysis of the participants' research histories. The comparative analysis will use the method of agreement and the method of difference proposed by Mill (2024). These methods focus on identifying the similarities and differences between cases in order to establish potential causal relationships (Ragin, 2014).

2.6.5.2 Application of comparative methods

By applying these comparative methods, the study aims to identify the common themes, methods and findings that cut across the participants' research backgrounds (method of agreement), as well as the unique aspects of each participant's expertise (method of difference). This approach is consistent with the principles of multiple case study analysis, which involves the systematic comparison of cases to generate insights and build theory (Yin, 2009, Berg-Schlosser, 2015).

2.6.5.3 Key questions addressed by comparative analysis

The comparative analysis will address several key questions:

-What are the main areas of convergence and divergence in the research expertise of the participants?

-How might these similarities and differences influence their perspectives on the use of interactive storybooks for language learning?

-What are the potential implications of the diversity of expertise for the design and interpretation of the Delphi survey?

2.6.5.4 Implications for the Delphi survey

By comparing the expertise and interests of the participants, this research will create a map of the landscape of knowledge and perspectives available for the study. The comparative analysis will help to inform the Delphi survey by drawing on the range of expertise of the participants and to support the interpretation of the survey results by taking into account the diverse backgrounds of the participants (Ragin, 2014).

2.6.6 Relational analysis

2.6.6.1 Applying SNA principles and techniques

Finally, the study will conduct a relational analysis to map the connections between the participants' diverse areas of research. While a social network analysis (SNA) (Wasserman and Faust, 1994) is beyond the scope of this study, the research will employ key principles and techniques of SNA to inform the relational analysis.

2.6.6.2 Exploring collaboration, knowledge sharing, and synergies

Specifically, the study will explore the patterns of collaboration, knowledge sharing and potential synergies across the multiple research areas represented by the participants. This will involve examining the co-occurrence of research topics, methodologies, and key concepts across the participants' research histories (Van Eck and Waltman, 2014).

2.6.6.3 Informing the Delphi survey design and interpretation

The findings from this relational analysis, although not as comprehensive as a formal SNA, will inform the design and interpretation of the Delphi survey. Understanding the interrelationships between participants' research areas will help to identify the key themes and issues to be covered in the survey (Mead and Mosely, 2001). The relational data will also provide a basis for assessing the degree of consensus and divergence in participants' views, taking into account their shared research interests and expertise (Landeta, 2006).

2.6.7 Contributing to the rationale for participant selection

Through these analytical steps, the study aims to develop a contextual understanding of how each participant can contribute to this research, based on their expertise and relationships with other participants' research areas. Incorporating the results of this analysis into the research report will support the rationale for the selection of participants and provide evidence of the relevance of their combined insights to the research topic.

2.7 Data analysis

2.7.1 MAXQDA: A strategic tool for analysing Delphi survey data

The qualitative data analysis software MAXQDA is used in this study to systematically analyse the data collected from the Delphi survey (Kuckartz and Rädiker, 2019). While MAXQDA is frequently used to analyse interview or focus group data (Oliveira et al., 2013), this study uses the software as a strategic tool to analyse information about potential participant groups of the Delphi survey (Paulus et al., 2013). The software's features for qualitative and mixed methods research, flexibility in importing and analysing various types of data, and interactive data visualisation capabilities make it suitable for processing and analysing survey data related to participant selection and categorisation (Saldaña, 2021).

2.7.2 Supporting diverse coding strategies and participant analysis

MAXQDA supports different coding strategies, including both inductive and deductive approaches, which is consistent with the methodological basis of this study (Jackson and Bazeley, 2019). The software's ability to facilitate detailed and sophisticated coding of information about potential participants is particularly valuable, as it enables the identification of key themes and patterns that can inform the selection and categorisation of participants (Cho and Lee, 2014). For instance, using MAXQDA's 'Code Matrix Browser' feature, researchers can visualise the frequency and distribution of codes across different participant groups, helping to identify similarities and differences in their expertise and research focus (Kuckartz and Rädiker, 2019).

2.7.3 In-depth comparison and contrasting of participant profiles

In addition, MAXQDA features such as the 'Code Relations Browser' and 'Document Comparison Chart' facilitate in-depth comparisons and contrasts of potential participant profiles (Kuckartz, 2019). The 'Code Relations Browser' helps to visualise the co-occurrence of codes, revealing potential connections or overlaps in participants' areas of research (Kuckartz and Rädiker, 2019). Similarly, the 'Document Comparison Chart' helps researchers compare coding patterns across different participant groups, emphasising the unique characteristics of each group (Kuckartz and Rädiker, 2019). These features support the strategic selection of diverse and relevant expert panels (Woods et al., 2016), providing a better understanding of potential participants and facilitating an informed and balanced participant identification process.

2.7.4 Enhancing reliability, validity, and transparency

The use of MAXQDA enhances the reliability and validity of the research by enabling systematic and consistent analysis of data relating to potential participants (Jackson and Bazeley, 2019). The software's capability to document and visualise the coding process increases the transparency of the data analysis, providing a clear audit trail of the analytical decisions made throughout the study (Kuckartz and Rädiker, 2019). This transparency enhances the credibility of the participant identification process in this Delphi study, as it makes it possible for readers to understand and evaluate the basis for participant selection and categorisation (Cho and Lee, 2014).

2.7.5 Supporting the iterative process of data collection and analysis

Finally, the use of MAXQDA is in line with the theoretical basis of the study, which involves an iterative process of data collection and analysis (Kuckartz, 2013). The comprehensive and versatile features of the software support this iterative process by helping researchers to easily revise and refine coding schemes as new data are collected (Saillard, 2011). This is particularly valuable in the context of a Delphi study, where participant selection and categorisation strategies may need to be adapted based on insights acquired from each round of data collection (Okoli and Pawlowski, 2004). MAXQDA's ability to facilitate this iterative and adaptive analysis process makes it a valuable tool in supporting the theoretical and methodological basis of this study.

3. Results and discussion

3.1 Description of expected research expertise

3.1.1 Definition of interactive storybooks and their potential for language learning

-Designing interactive storybooks

The research aims to explore the potential of interactive storybooks as a tool for enhancing English language skills, particularly for Key Stage 3 (KS3) students in the context of the secondary English literature curriculum.

-Enhancing language learning through multimodal content

Interactive storybooks are digital narratives that combine text, images, sound and interactive elements to create an immersive and engaging reading experience (Sargeant, 2015). They have been identified as supporting language learning by providing multimodal content, encouraging positive engagement, and promoting learner independence (Takacs et al., 2015, Kao et al., 2016).

-Contributions from multidisciplinary experts

Experts in various fields such as digital culture, interactive media (Gee, 2003), technology-integrated storytelling (Lambert and Hessler, 2018, Robin, 2008, Miller, 2019), and data-based pedagogical methodologies (Mayer, 2005a) can contribute to this research initiative. Their collective knowledge not only provides insights into the technical aspects of designing and implementing interactive storybooks, but also emphasises the pedagogical implications of using such tools.

-Bridging traditional and digital pedagogies

By bridging the gap between traditional literary studies and contemporary digital pedagogical approaches, interactive storybooks can provide KS3 students with a comprehensive educational experience that focuses on the development of their English language literacy (Lim, 2020, Hsiao and Shih, 2015).

3.1.2 Researchers by university department

3.1.2.1 Diverse perspectives from different disciplines

The research involves researchers from a variety of university departments that are related to the focus of the project (Flewitt et al., 2015). These include departments such as media, interactive media (Serafini and Gee, 2017), media production, media and communication (Kress and Van Leeuwen, 2001), digital media (Livingstone, 2012), publishing media, media and creative industries and multimedia storytelling (Jenkins, 2009). Each discipline brings a different perspective to the interactive storybook project, broadening the scope of the research.

3.1.2.2 Contributions to research methodology and content design

Researchers from media and communication departments provide valuable insights into students' media consumption habits and preferences, which can inform the creation of engaging and linguistically appropriate content for interactive storybooks (Alper and Herr-Stephenson, 2013). Similarly, experts in interactive media and multimedia storytelling can provide guidance on the design of immersive and interactive features that can enhance language learning opportunities (Hirsh-Pasek et al., 2015).

3.1.2.3 Expertise in technology integration and evaluation of effectiveness

Researchers from digital media and publishing departments can contribute their knowledge of current digital platforms and the publishing landscape, which is important for the effective distribution and accessibility of interactive storybooks (Siegenthaler et al., 2011). In addition, researchers with expertise in data-based pedagogical methodologies can contribute to the development of feasible frameworks for evaluating the effectiveness of interactive storybooks in language learning contexts (Mayer, 2017).

3.1.2.4 Theoretical and pedagogical foundations

In summary, researchers from university departments focusing on education, media, interactive media and other relevant fields provide a range of academic perspectives on the use of interactive storybooks for language learning (Kucirkova et al., 2014). Their expertise can contribute to understanding the theoretical and pedagogical foundations of integrating such tools into the language learning process, as well as the potential benefits, challenges and overall feasibility of this approach (Bus et al., 2015). Their familiarity with current research trends and understanding of the educational and digital media landscape can add insight and value to the findings of the study (Hoffman and Paciga, 2014).

3.1.3 Researchers in the personal network

3.1.3.1 Multidimensional expertise and practical experience

The involvement of researchers from the personal network promises to contribute a multi-dimensional approach to the research project, as they provide a range of expertise and practical experience in the use of interactive storybooks for language learning (Wohlwend, 2015, Korat and Shamir, 2012, Lieberman et al., 2009)

3.1.3.2 Theoretical basis and pedagogical insights

Dr P6H, known for her expertise in educational philosophy and her influential work on the ethics of care in education (Gregory et al., 2017), can provide an in-depth understanding of the theoretical foundations behind the use of interactive storybooks for language learning. Her knowledge of teaching and learning methods, early years and primary education, and ethics in education (Haynes, 2008) is likely to provide valuable insights into the pedagogical foundations of the project.

Dr PHP, with his focus on digital learning and technology-enhanced learning will provide key insights into the effective integration of interactive storybooks into educational context. His research on the design and evaluation of digital pedagogical tools and his work on learning spaces provide valuable resources for optimizing the implementation of interactive storybooks in classrooms (Pratt et al., 2015, Waite and Pratt, 2017).

3.1.3.3 Narrative and storytelling expertise

Dr P3C, an acclaimed author and creative writing educator and P2K’s expertise in creative writing and literature can provide insights into how narrative and storytelling can enhance language skills. Their teaching experience will provide practical knowledge about integrating interactive storybooks into the classroom (Caleshu, 2012, Kiernan, 2021).

3.1.3.4 Digital media design and interdisciplinary perspectives

P8C's expertise in digital media design and other contributors, including Dr P5G, Dr P13W, Dr P7Q, Dr P11M and Dr P9S, will shape the implementation, design and impact of these interactive storybooks. Their unique perspectives and skills are expected to be invaluable to this project (Campbell-Barr et al., 2015, Allen et al., 2013, Pettit et al., 2015).

3.1.3.5 Early childhood studies and learning development expertise

Finally, this study looks forward to the insights of Dr P14H, Dr P14P, Dr P12K and Dr PS1. Their expertise in early childhood studies, academic development, comparative education and learning development will contribute to the effective design, implementation and evaluation of our project. Their involvement will make sure a multi-faceted approach to our research into the use of interactive storybooks for language learning (Kelly et al., 2012, Gibson et al., 2019, Syska and Buckley, 2023).

3.1.4 Researchers identified by keywords

3.1.4.1 Keyword selection and relevance to research objectives

This category includes researchers identified through a keyword-based strategy that reflects the core themes and concepts of the study. The key components of the study are reflected in the selected keywords - storytelling, digital storytelling, education, KS3 students, GCSE examination, curriculum enrichment and multimedia. These keywords were carefully selected to be in line with the research objectives and to help identify researchers with expertise directly relevant to the study (Maxwell, 2012, Creswell and Creswell, 2017, Bryman, 2016).

3.1.4.2 Insights from keyword identified researchers

-Expertise in digital storytelling and language learning

Researchers within these keyword areas can provide important insights related to the primary research objective. For instance, experts in 'digital storytelling and language learning' can provide useful perspectives on the effective use of interactive storybooks to enhance language skills (Robin, 2008, Smeda et al., 2014).

-Guidelines for technology integration in education

Similarly, researchers specialising in 'technology in education' can provide guidance on the appropriate integration of digital tools, such as interactive storybooks, into educational environments (Hew and Brush, 2007, Ertmer and Ottenbreit-Leftwich, 2010).

-Focus on inclusive education and diversity

Other potential keywords identified in this review, such as 'inclusive education and diversity' and 'professional development', recognise the broader educational context of the research. They indicate a focus on making sure that the use of interactive storybooks is inclusive and that teachers are prepared to integrate this technology into their pedagogical practice (Artiles, 2013, Voogt et al., 2013).

-Curriculum development and integration

The keyword 'curriculum development and integration' emphasises the importance of integrating interactive storybooks into the existing curriculum in order to maximise their educational impact (Fadel et al., 2007).

3.1.4.3 Advantages and challenges of the keyword approach

-Advantages of the keyword approach

The keyword approach provides the research with a diverse and knowledgeable group of participants, providing the research with scope and depth. The inclusion of researchers from different keyword areas provides the study with a wide range of perspectives and expertise, which is important for developing a comprehensive understanding of the use of interactive storybooks for language learning (Bryman, 2016, Maxwell, 2012, Creswell and Creswell, 2017).

-Recognise and respond to potential challenges

However, potential challenges associated with this approach are recognised, such as coordinating with participants from different geographical locations and accommodating different viewpoints (Keeney et al., 2001).

-Using the Delphi survey method to respond to challenges

To alleviate these potential barriers, this study will use the Delphi survey method, a structured communication technique that facilitates consensus building among a panel of experts (Turoff and Linstone, 2002). The Delphi method is adapted to the objectives of this study as it facilitates the systematic collection and synthesis of expert opinions, leading to comprehensive understanding of the research question (Hsu and Sandford, 2007, Baker et al., 2006).

3.1.4.4 Conclusion: A foundation for research

In conclusion, the diverse pool of potential experts identified through university affiliations, personal networks and keyword searches provides a substantial foundation for this study. Their expertise spans a wide range of relevant areas, including digital storytelling, language learning, educational technology, inclusive education, teacher professional development and curriculum integration. This range of expertise will be instrumental in supporting the key challenges of designing interactive storybooks for language learning, making them accessible and inclusive, and integrating them into the existing curriculum.

3.1.5 Flowchart of participant categorisation

Figure 8 provides a visual representation of the systematic approach used to select and categorise participants for the Delphi study. The flowchart illustrates to secure a diverse range of expertise and perspectives (Okoli and Pawlowski, 2004).

The participant selection process begins with the identification of relevant keywords that reflect the core themes and concepts of the study, such as digital storytelling, language learning and educational technology. These keywords are used to conduct a search and identify potential experts in the area (Hsu and Sandford, 2007). The keyword-identified researchers are then screened and selected based on the relevance of their work to the objectives of the study, as determined by their publications and research focus (Skulmoski et al., 2007).

At the same time, the primary researcher's personal academic network is used to identify potential participants. Researchers within this network are assessed based on their expertise and interest in the topic of the study, and those who can provide valuable insights and have a direct interest in the research area are included (Keeney et al., 2011).

The third category of participants is identified by selecting university departments that focus on relevant areas such as media studies, digital media and educational technology. Researchers within these departments whose work is relevant to the aims of the study are then identified and included in the pool of potential participants (Donohoe et al., 2012).

Once researchers have been identified, they are grouped into three main categories: keyword-identified researchers, personal network researchers, and university departmental researchers. The combined list of researchers is then reviewed to provide a balanced representation of expertise across the different categories (Powell, 2003).

Finally, invitations are sent to the selected researchers and their responses are collected. The list of participants is completed based on their willingness to participate in the Delphi survey (Day and Bobeva, 2005).

By following this systematic approach, the study aims to assemble a diverse and knowledgeable panel of experts who can contribute valuable insights to the research questions under consideration.

3.1.6 Diagram of bias mitigation strategies

Figure 9 provides a visual representation of the strategies employed in this study to mitigate potential bias and secure the credibility and validity of the research findings. The diagram emphasises three main strategies: reflexivity (self-reflection), methodological triangulation and transparency arrangements (Berger, 2015, Noble and Smith, 2015).

Reflexivity involves continuous self-reflection by the researcher to identify and account for personal biases and assumptions that may influence the research process (Dodgson, 2019). This strategy includes maintaining a reflexivity journal, engaging in peer debriefing, conducting regular self-assessments, and integrating reflexivity into data analysis (Darawsheh, 2014).

Methodological triangulation involves the use of multiple methods of data collection and analysis to cross-check and validate research findings (Denzin, 1978). This strategy includes combining qualitative and quantitative methods, using different data sources, cross-checking data and involving multiple analysts to increase reliability (Hussein, 2009, Jick, 1979).

Increasing transparency involves providing a clear and detailed account of all research processes, decisions and methodologies to facilitate scrutiny and replication by others (Aguinis et al., 2018). This strategy includes detailed methodological documentation, providing access to raw data, clear reporting of findings, and maintaining open communication with research participants and stakeholders (Moravcsik, 2014).